How Les Misérables Landed in Caracas

It was already ambitious of young producer Claudia Salazar to attempt the staging of the great musical based on the novel by Victor Hugo, let alone doing it in 2019 Venezuela. Now that it returned to the Teresa Carreño on March 30th, we tell this incredible story

Photo: Sofía Jaimes Barreto

Traveling up the long escalators that lead towards the entrance of the Ríos Reyna hall, under the gaze of the massive Jesús Soto piece decorating the ceiling of the Teresa Carreño theater, usually comes with a certain nostalgia for that modernist Venezuela of reinforced concrete, international theater festivals, and yearly seasons of the The Nutcracker. Despite the dim light from the lamps that illuminated the common areas and the darkness emanating from the entrance to the parking lot, the traditional red sweaters of the guides gave a feeling of familiarity that was comforting. The audience arrived shyly, like someone who enters their childhood home when other people already live there. Asking for permission, going to see if the walls and doors have not moved. This is how it looked for those who in October 2019 reunited with that space to watch the last performance of Les Misérables in Caracas.

Before moving on with this story, it is important to make it clear that there cannot be any spoilers when writing about Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Jean Valjean’s redemption tale is the archetype of the modern redemption story: a man who escapes from prison to become a righteous mayor, an inspector who spends decades on his trail, love, heartbreak, forgiveness, everything. Wrapped up in the context of a post-pandemic Paris ignited by student-led protests. It has been taken to countless formats and has been told in all the ways that a story can be told. And whether Valjean is known from the novel, or from the movies, or whether we see him with the face of Liam Neeson or Hugh Jackman, one of the most celebrated formats has been the musical adaptation by Claude-Michel Schonberg and Alain Boublil. There are dozens of movies, TV series, sequels, comics, and manga, and it has been the inspiration for other great stories that revolve around the work. Great stories like this one, which begins, precisely, with an arrow launched into the air.

The Arrow

Claudia Salazar already had experience producing musicals. She worked in Jesus Christ Superstar and had produced the musical The Sound of Music. At the age of 30, she had already made a name for herself in the theater scene. So much so, that once the very dear Carmen Victoria Pérez affirmed that having Claudia behind the scenes was a “seal of quality.”

Venezuela has a solid, but timid, theatrical tradition. Good writers and great actors. Piaff and Señora Imber are two good recent examples. But in general, and especially in recent times, it is low-risk theater. Productions that do not require too many parts moving at the same time, that do not have many expenses, and that can be solved without much production. It makes financial sense.

“Les Misérables was the dream”, says Claudia, “but I saw myself pulling it off at 60, already as the achievement of a lifetime producing musicals. And if it had been so, I would consider that I had a successful career and I would retire happy. You have to understand this: it’s not as if you can wake up one day and say let’s go do Les Mis.” Apart from the difficulty of putting together the production, there are a series of bureaucratic obstacles to overcome that seem almost impossible.

The first step: asking for the rights. In mid-2017, Claudia found out that the rights to the work were available and wrote to Music Theater International (MTI) in London, the company that manages them. She introduced herself, and told them what she wanted. They very formally explained the steps and requirements. She had to show her credentials as a producer and start checking the boxes. And so began a slow exchange of emails, which lasted for several weeks, during which Claudia was responding to what was asked of her.

And one day, an unexpected email arrives. “Congratulations,” they approved the request. She had the rights available for 10 functions. Claudia read and reread the mail and couldn’t believe it. But little by little the joy of the nearness of her life’s dream was replaced by a terrible anguish: “now what?”

She borrowed what she could and used her savings to pay for the rights, and then gave herself a mental cushion by postponing the next move until the time production of Piaf wrapped up. Fortunately, she was in the middle of the staging and was able to establish certain limits to focus her attention on what she had to.

Already into 2018, she was able to sit down and measure the magnitude of what was in front of her, and it was a dream that could easily turn into a nightmare. She started with the basics. She got a necessary partner and accomplice at FM Center. Then, she submitted the theater for the approval of MTI, which was not very difficult since Teresa Carreño, battered as it was, more than meets the credentials. For music, she had to look no further than the Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho Symphony Orchestra directed by Elisa Vegas. Also, Elisa and Claudia had worked together on The Sound of Music and it was a perfect fit.

The Ensamble

More difficult than theater and music would be to find a director who met the requirements, and who was willing to sign up for the odyssey of putting together one of the most important Broadway musicals in the country with the most depressed economy in the world. The names that Claudia sent to London bounced off one after another. Venezuelans, Spanish, of different nationalities and different experiences. Nothing. Until the same company told her about an Argentinean director who lived in London, who had already directed the work, and with whom they had had very good results: Mariano Detry.

Mariano saw that as a great challenge and, well, for what it was: an adventure. He said yes and went on board.

The logistics to assemble all the pieces of this enterprise, without them falling along the way, was not easy. But with a director on the team, they could start working on finding the cast. They made the call through social media and with a couple of spots on the radio. The response was massive. Thousands of people answered.

People from all over Venezuela applied. And after an arduous process filtering the applications, they found the first group for the auditions. They saw 700 people, just as if they were holding The Voice auditions, in something that was far from a traditional vetting process in Venezuela. Claudia managed to get El Sistema to give them the space at the Center for Social Action for Music for the auditions.

When the candidates entered that space, with the chairs designed by Cruz Diez and Tomás Lugo’s architecture, they were dazzled. The process was like none those actors had seen before. When it was their turn, they would go up on stage and greet them by name. Then they were given the opportunity to perform the part of the play they had prepared. Everything very formal and orderly, until Mariano changed the tune.

Mariano wanted them to improvise something that everyone knew, a deeply rooted song, something epic. And when he heard the national anthem for the first time, he said “this is it.” But to fully understand what would happen next, you have to remember the context in which this happened. We are talking about Venezuela at the end of 2018: the end of years of student protests that took place in the streets. The group, for the most part, were young people in their twenties. And there was Mariano, asking them to feel the national anthem, to sing it defiantly, as if their future depended on it.

Claudia says that moment was one of the most moving of the entire selection process. “Of course, Mariano didn’t know what he was asking of those kids, for most of them it was something very personal.”

Mariano was amazed upon entering the theater. Moved by these young people, he ended up hopelessly in love with Caracas.

The chosen cast was a melodious mix of accents and talents. The role of Jean Valjean fell into the hands of Humberto Baralt, a 26-year-old with a booming voice and a great ability to transform—a key skill since it is essential to achieve all of Valjean’s own metamorphosis. His counterpart, Inspector Javert, went to a broadly respected performer called Gaspar Colon.

The Master of the House

Photo: Hiram Vergani

They did their work, they took ownership of the cause of those French students with whom they identified so much, so much so that there were many tears and and high emotions during rehearsals, and they held on to this project as if their lives depended on it.

The Light Goes Off

Rehearsals began in January, they had to run because the date set for the premiere was May 23, 2019. The situation in Venezuela was not easy, but the project gained traction. Different private sponsors that fell in love with it jumped on along with a key ally: the French ambassador in Venezuela.

Les Mis went on despite what was happening in the country. Juan Guaidó, the president of the National Assembly, was sworn in as caretaker president and public attention was fixed on the Venezuelan border with Colombia and an event that was organized to bring humanitarian aid to the country. In the midst of this politically charged environment, the team advanced without looking to the sides.

And then, March 2019 arrived and the power went out. Caracas plunged into darkness for almost three weeks, and other regions of the country for months. They tried to handle it the first few days, but as time went by, the folks from London started wondering what was happening in Venezuela.

Claudia managed to establish communication with them and they came to the conclusion that the release date had to be moved. New date: October 31, 2019. This would allow them to get organized and let time pass to get an idea of whether the situation in Venezuela could stabilize enough to actually stage the play.

The London crew, including Mariano, planned a trip to Caracas to work with the cast and orchestra. Now, with the new date set they could work calmly. So they landed in Venezuela on April 29th. All’s fine.

During the early hours of April 30th, a video of Juan Guaidó appeared on social media, together with Leopoldo López and a small group of Venezuelan soldiers declaring themselves in rebellion. It was a confusing moment, it was not clear if it was a military uprising or what. They flew over the deserted motorways to take the group from London to the airport, put them on a plane and say goodbye.

“Are you going to continue?” Claude-Michel, the composer of Les Misérables, asked Claudia in an email.

“Yes, we will.”

She was invited to London, and on the trip she was able to meet Thomas Schomberg, Claude-Michel’s son, and Cameron Mackintosh, the legendary Broadway producer and Claudia’s personal hero. That was on May 27th. After all the stress of those weeks, the trip gave her a much-needed dose of encouragement. She was greeted as an equal, Mackintosh gave her a hug, they genuinely stepped up and gave her their full attention moving forward.

Meanwhile, on the Venezuelan side, Claudia had many problems to solve. The air conditioning system of the Teresa Carreño was not working and they had to find a solution. The play lasts almost three hours and they couldn’t have the audience there, roasting. But making the necessary repairs to the theater would cost over a million dollars. The solution? They rented 33 small air conditioning units so that the temperature in the legendary Ríos Reyna hall would be tolerable.

During the first rehearsal at the Teresa Carreño, water from a storm flooded the musicians’ pit and turned it into a swimming pool. They were solving problems on the fly while working at full speed with the cast.

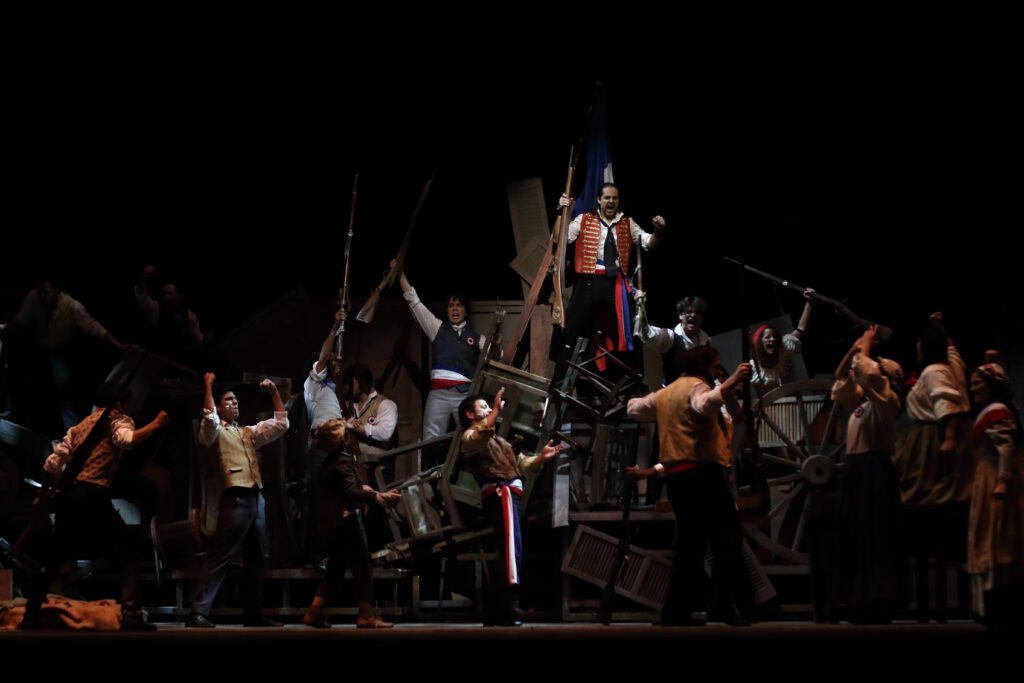

But just as the place posed many challenges, it also brought great surprises. The set was made entirely in the theater’s workshop. They did a great job with the barricade that the French students build, which is a very important piece during the play. They collected furniture from colle all over Venezuela and the result was a truly impressive structure.

The Barricade includes furniture from all over Venezuela

Photo: Hiram Vergani

We’re all Les Misérables

As the months passed, the cast became increasingly sharp. They no longer fell apart during the scenes. They managed to control their emotions, even though they were there, on the surface. It was starting to feel as if this was going to be something truly special. Les Mis was going at full speed.

And that’s how even Claude-Michel Schonberg himself ended up in Venezuela helping to prepare the musicians, without charging a cent. He was curious about what was being reported from Caracas and he became infected with enthusiasm for the project. Also, he had been to Venezuela in the 1970s and remembered the country very fondly.

Claude-Michel Schonberg holds the microphone for Mariano Detry, the director of the play, as Claudia Salazar watches from the left.

Photo: Hiram Vergani

When the sheet music arrived, the box seemed a little too small. There were only 16 sheets and they had the entire Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho orchestra at their disposal. But when they wrote to ask for the rest, from London they said no: “The play is written for 16 musicians.” And of course, the music has been performed by full orchestras countless times, but the play is done with 16. The team insisted. They proposed to make an esteroid version of Les Mis, they asked for an exception. The obvious and logical answer was a resounding “no.” However, after a few weeks, Mariano calls Claudia: “you won’t believe this.” They had reconsidered, and were composing the score for the rest of the orchestra. Les Mis in Venezuela would open with 32 musicians for the first time in the history of the musical.

MTI had also given permission for “Do you hear the people sing?” to be sung. Musicals abide by very strict rules. When the score ends, the music stops. But in this case, Schomberg himself gave permission for the cast to sing the song on stage after the bows, with the intention that the audience would join them. “These people need it.”

This combination of concessions mixed with the talent and connection of the performers—and even the public—with the play caused a before and after for Les Misérables and for Venezuelan theater.

Rodrigo, a Cuban artisan who has worked in the TTC workshop for more than 35 years, summed it up better than anyone: “Les Mis brought the light back to the Teresa Carreño.”

The Return

This previously unpublished interview took place back in December 2019 after Claudia finished the production of Les Misérables. She had set her own bar very high and accomplished a near impossible feat. There were 10 successful performances and it was an encouragement for those who were lucky enough to see it at a time when the country needed it.

“I want to be an accomplice in the development of musicals in Venezuela,” Claudia said as a conclusion to that conversation. And she has been.

Now, Les Misérables returns to the Teresa Carreño, whose facilities have been renovated, with a contagious drive and an experienced team. The original cast is joined by a cohort of extremely talented young people and Mariano Detry returns as director. I will not weigh in on the quality of the play, because now, I am too “an accomplice.” I just wanted to tell this incredible story. The new season started on March 30th and will run through April. Tickets available here

This post was first published in Spanish in Cinco8 and is the product of an alliance between Caracas Chronicles, Clas Producciones and NVIVO.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate