Capriles and the Death of the Old Guard

The man who almost defeated Chavismo ten years ago checked out of the opposition primary election race with dwindling numbers and a weak excuse

On Sunday night, Henrique Capriles Radonski took to his social media accounts and told his followers that he was dropping out of the opposition primaries, barely 14 days away, because he was still barred from running for office. He added that Primero Justicia, the party he helped create two decades ago, would be left with the decision to choose a candidate.

There had already been some noise coming out of the Primero Justicia camp since Friday, when the party called for a meeting of the National Political Committee. A meeting that was never held, but that generated rumors that poured through Saturday and were finally put to rest by Capriles himself, confirming the suspicions. Thus ends a campaign that never managed to go further than the short burst it received by the wave of nostalgia that first carried it.

Let’s take a look back at the rocky history of his latest presidential push, so we can then look forward to what it means for a generation of politicians who shaped our understanding of Venezuelan politics over the last two decades.

Campaign by Committee

Over the past few years, it’s been hard not to see Capriles as another iteration of Venezuela’s long line of messianic leaders. His behavior, at times, showed him as someone more than happy to play into that perception, publicly presenting himself like a maverick-prophet who would carve the path to salvation. This latest cycle began with the very moment his party nominated him as their candidate for the 2024 election by calling him “a gift for Venezuela.”

Capriles tossed his hat into the ring because he believed he carried the historical weight to win. He believed he could recapture those lightning-in-a-bottle moments from a decade ago, but he knew this same history could play against him. His first big move was to try and absolve himself of any blame by dropping an hour-long propaganda video on YouTube replaying the highlights from those years. In it, he tried to shift the blame for what happened onto others—like Leopoldo López and María Corina Machado—by playing clips of them supporting his decision to not fight out the 2013 election results in the streets. The final third of his “documentary” would use the 2014 and 2017 protests to claim he made the right call. Of course, those clips leave out his own leadership in the protests, at least during the second wave.

Inexplicably, after this moment of historical revisionism, his campaign would put out all sorts of weird messaging. We had the ¿Quién es el Flaco? Pokémon-inspired “intrigue” campaign. We had a strange attempt at setting a TikTok trend with a fake fan account run by the women who… um, fancied him. And who could forget that campaigning video set to the music of Silvestre Dangond’s Sigo Siendo el Papá. Was he? Maybe a decade ago. But now he was looking like someone desperate to be remembered for the glory of his past.

Left Behind

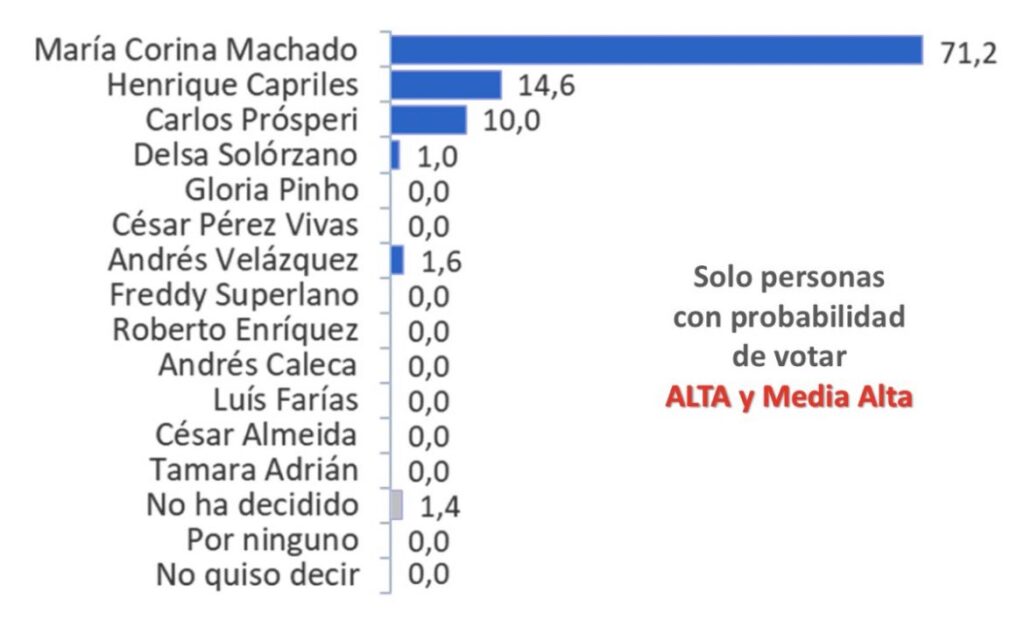

All that noise certainly helped him get his name back up high in Google search results and local Twitter trends, but it probably didn’t help him in securing more votes than his rivals. Slowly but surely, Capriles began falling further and further back in the polls. While in most polls he still hung on to that number two spot, the gulf between him and Machado only continued to grow. What’s most odd is that, at times, he didn’t even seem interested in closing the gap.

For starters, Capriles didn’t participate in the primaries debate held at the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB) on July 12th. He’d justify this decision, saying a debate would only “deepen existing divisions” and even letting out a backhanded criticism of the event by asking how many television channels would cover it, pretending to forget the government’s heavy hand on local media. He’d also refused interviews and appearances where he didn’t entirely control the narrative.

In the eyes of many of those who voted for him in 2012 and 2013, Capriles has become a symbol of a political elite—incapable of ousting the regime

Three months after the debate, Capriles quitted. He said, on a post on social media and during his announcement livestream, that his decision to drop out was because he was still barred from running for office. A strange reason considering that, unlike María Corina Machado, he definitely knew he was barred from running the moment he announced his candidacy. Some commentators on social media have hailed Capriles’ decision as a “responsible” one, some going as far as to say it proves Capriles isn’t in it for his own sake but that he’s clearly thinking about the country’s future. The reality of the situation, however, is that Capriles’ campaign never picked up enough steam to win. None of the big polls in recent times have even placed him close to Machado, let alone in front.

Capriles is taking the toll of being the old guard’s poster child. Ten years after the 2013 presidential elections, el flaco is no longer the young and energetic good-looker who brought hope to opposition voters. He is now a middle-aged man, stained by an electoral defeat that an important part of the opposition electorate perceives as a fraud unfought. In the eyes of many of those who voted for him in 2012 and 2013, Capriles has become a symbol of a political elite—incapable of ousting the regime—that Machado, once a radical option on the fringes of the opposition’s electoral buffet, is now promising to swept aside.

What Comes Next?

The opposition primary is the biggest democratic event in a decade and Capriles has only existed in the periphery of it, never feeling comfortable enough to make a big push for the lead. It seems as though he decided, long ago, to wait and see if party leaders found Machado unelectable and thus rallied around him instead. It’s now less than two weeks until the primary and that moment hasn’t arrived; Capriles has dropped out. This is a big moment for people like him and other members of the old guard like Manuel Rosales and Leopoldo López. I don’t doubt for a minute that they’ll jump at a presidential run in the future (even in the near future), but times have indeed slipped away from them.

Henrique Capriles almost beat Maduro in 2013. Now he can’t win a primary election. Manuel Rosales seems to be sitting comfortably in Maracaibo, watching over the kingdom Nicolás Maduro has allowed him to have. Leopoldo López isn’t even in Venezuela and bringing up his name in a political discussion is likely to get you laughed at. These were huge names once upon a time, and their parties—Primero Justicia, Un Nuevo Tiempo and Voluntad Popular—seemed like the future of Venezuelan politics. Back in January I wrote about how opposition parties didn’t have an identity of their own, but instead they were tied to that of their perpetual leaders. Many of those leaders can no longer bring success to their parties and the promises of a presidential win seem to have completely slipped away. So, we find ourselves at a sort of crossroads.

The downfall of the old guard could drag the parties down with them or it could provide them with a chance to finally find their own voices; to forge their own identities separate from that of their founders. This last electoral cycle has probably shown young voices within the traditional party structures that it may well finally be sink or swim time. While I’m sure many are frightened of what it could mean for their institutions, many are probably relishing the chance to finally be free.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate