According to Polls, the Primaries Raised Venezuelans' Spirits

Expert pollster Félix Seijas explains how the old culture of vote in Venezuela has resurfaced around this Sunday’s event, even after so much trauma and with enduring caution

“We are not going to see large caravans of people in the street. It is an atmosphere of electoral expectation”. With a keen eye on electoral dynamics, Seijas, who has a Ph.D in Analysis of Complex Data, leads Delphos, one of Venezuela’s top pollsters. Few days before October 22nd Venezuelan opposition primaries, he foresees the most likely turn up, dissects the intricate electoral patterns that emerged, and discusses how the primaries rekindled people’s commitment to the electoral process.

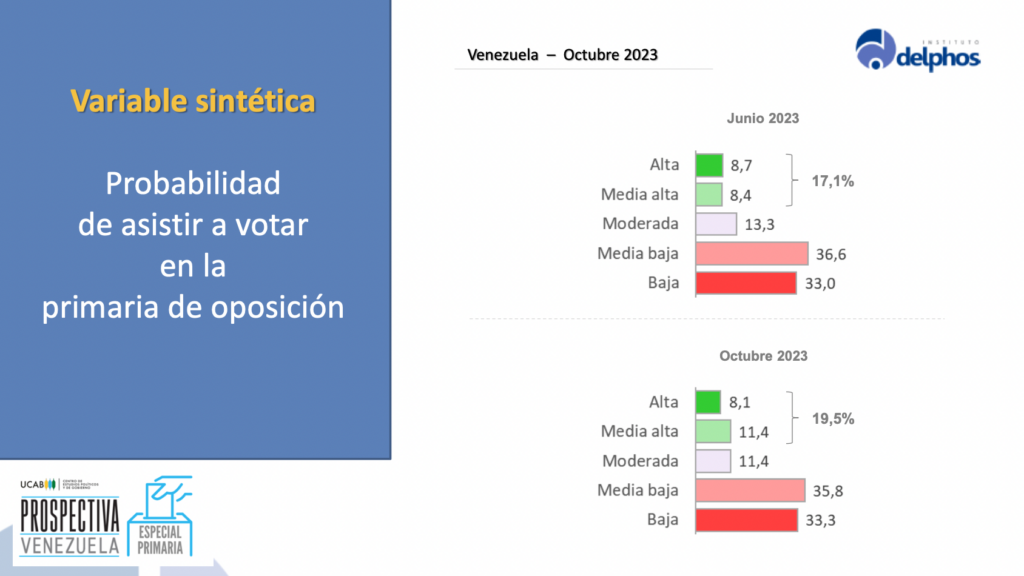

According to the Delphos surveys, is the willingness to vote in the opposition primaries high? Or has the primary not penetrated the population beyond the core opposition?

The current willingness to vote is around 8% of the electoral population living in Venezuela: that is, considering an electorate of 17 million and not the almost 21 million we used to have. Nowhere in the world a primary election has high participation percentages, but in 2012 we saw 16% of the electorate voting in a primary, and now we have a ceiling around 19%. This number, in these very adverse circumstances, is quite good after what has happened since 2012 in terms of expectations of change. However, one thing is the people willing to go to vote and another those who want the primary to turn out well, but are waiting to see what ends up happening. There we are talking about 60% of the Venezuelan population, who consider that the primary is the correct way to settle what they want: a single candidate. But many of them are not going to vote because they may be upset with the opposition or because they are waiting to see whether the opposition is being serious or not.

In a recent forum sponsored by Ecoanalítica, you mentioned that the primary –whether it happens or not– achieved its objective: to reawaken political interest in the population, the mobilization of the opposition electorate and new hopes for political change. Can you elaborate on this?

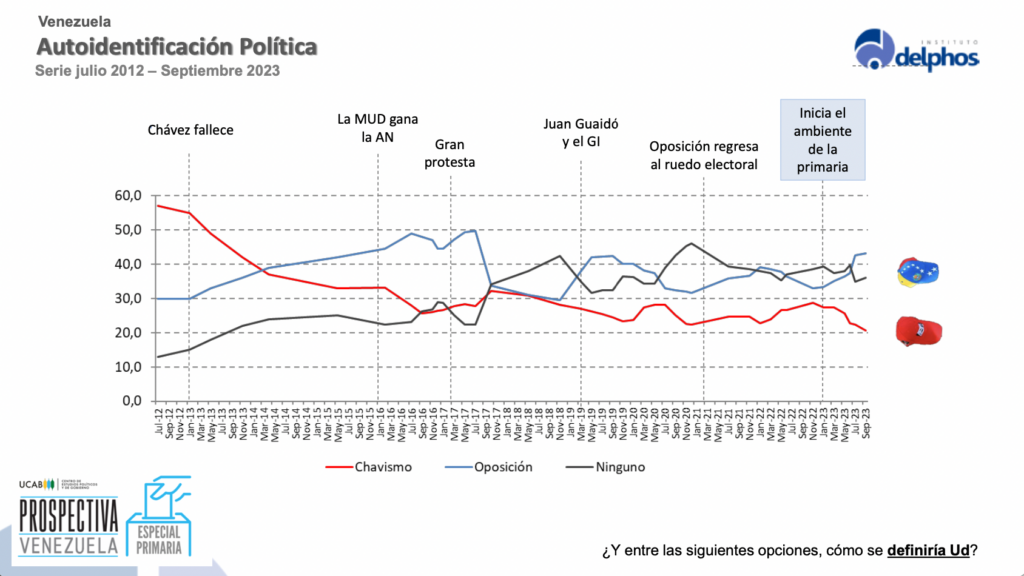

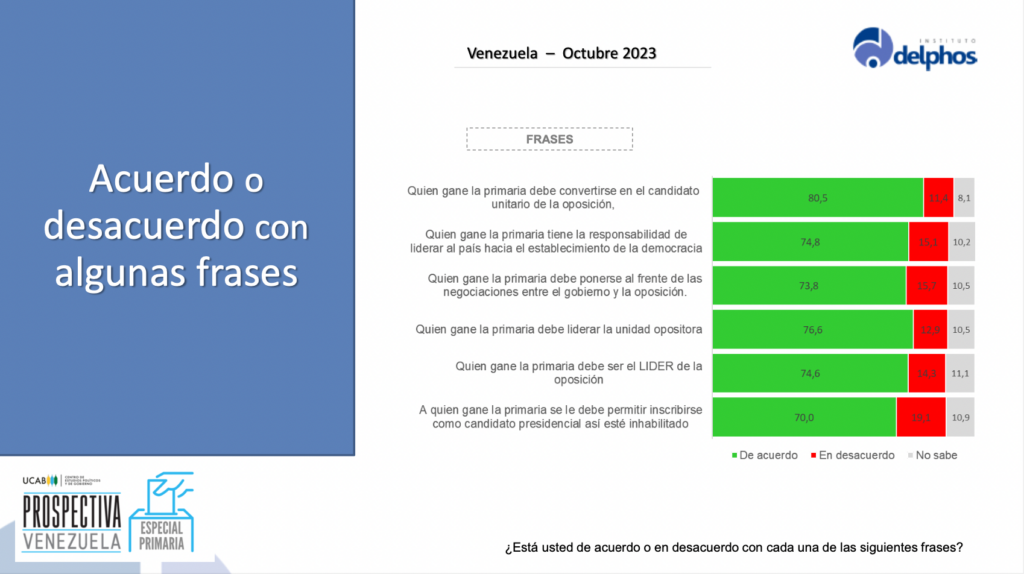

We come from several years of peak moments in which a great expectation of change collapses, and people feel betrayed and going backwards. A large part of the opposition mass started this year with low spirits, that nothing could be done now, that everything was lost, that the monster was too big to be confronted. Well, the primary changed all of this. It brought the 2024 election to the present, it made people feel there is some renewal process in the opposition leadership because of figures people may consider new, such as Carlos Prosperi and even María Corina Machado, who was in the reserve during the last years. This has raised people’s spirits, though people are still a little cautious. If the primary takes place and actually produces a single candidate… well, it’s done. Whether the primary electoral process occurs or not, we will have its benefits [regarding mobilization and high spirits].

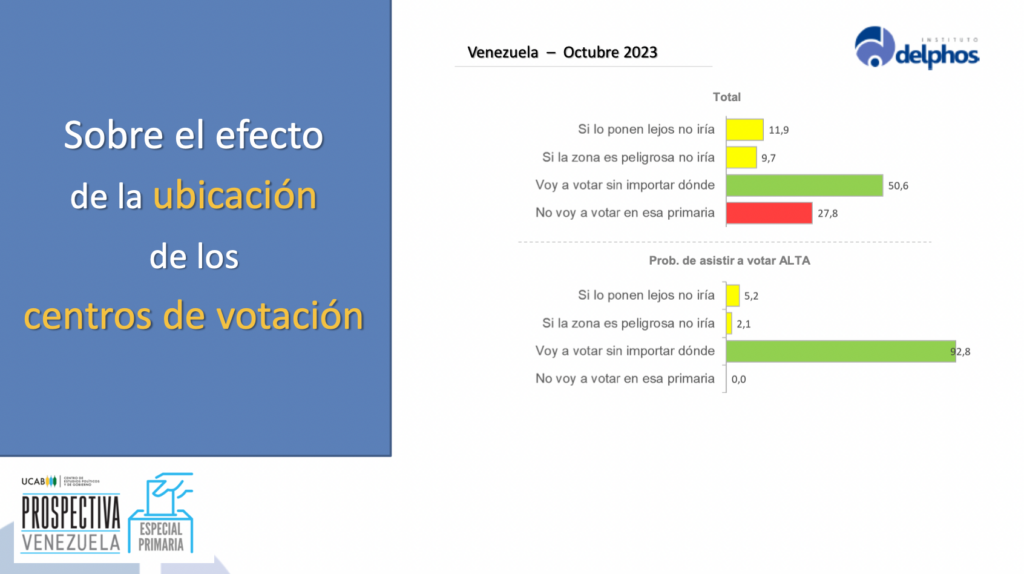

What is the likely number of voters on October 22, given the lack of knowledge of the voting centers selected by the National Primary Commission and different from the usual ones of the CNE?

There are challenges. But that 8% is going to find out where they vote, even if it is the same day. Capriles’ retirement also means that a machinery like Primero Justicia will not be very enthusiastic about putting resources into mobilizing people that day, but that 8% floor will stay, unless something public and notorious happens. What may change is the ceiling of voters.

Delphos shows that 67.3% of Venezuelans are sure to vote in 2024 and 22.9% would perhaps vote. Do these numbers show an increase since 2017-2020, years of electoral abstention by the mainstream opposition? Is abstentionism receding?

Willingness to vote in the next presidential elections shows that the [electoral] path is being resumed. In previous processes, for example the 2018 election, MUD decided not to participate, and that of course meant that a large part of the population did not end up showing up. The primary excites and opens up the expectation about an electoral process like the presidential elections is. If a unitary candidate is achieved, we will return to the traditional turn up figures: around 90% of the electorate, though in reality less people would vote in the presidential election because there is part of that electoral registry that is not in Venezuela anymore and has not been allowed to register [abroad].

How would the voting intention be affected if, once the primaries pass, other possible candidates like Manuel Rosales run for president anyway? How would the voting intentions for 2024 be affected if the primaries cannot be held, due to sabotage by the Supreme Court or internal conflicts in the opposition?

These are two different things: if the primaries are suspended for reasons attributable to the government or if they are suspended for reasons attributable to the opposition. If they are suspended for reasons attributable to the government, it is a little easier to handle the matter. If they are for reasons attributable to the opposition, we would have to see what those reasons are. But the background to all this is whether there is a unitary option. If the primary is suspended because a political party sabotages or because the TSJ issues a ruling or because things happen that day… If despite all this, the people and other actors support the main option—which is María Corina—because they feel that this forms a unitary organization, she will become the candidate as if it were chosen by the MUD in its good times. Likewise, if Rosales runs by himself, of course he is going to take some votes. But in the end, if the perception of a unitary option is consolidated, any other option ends up decreasing to small numbers.

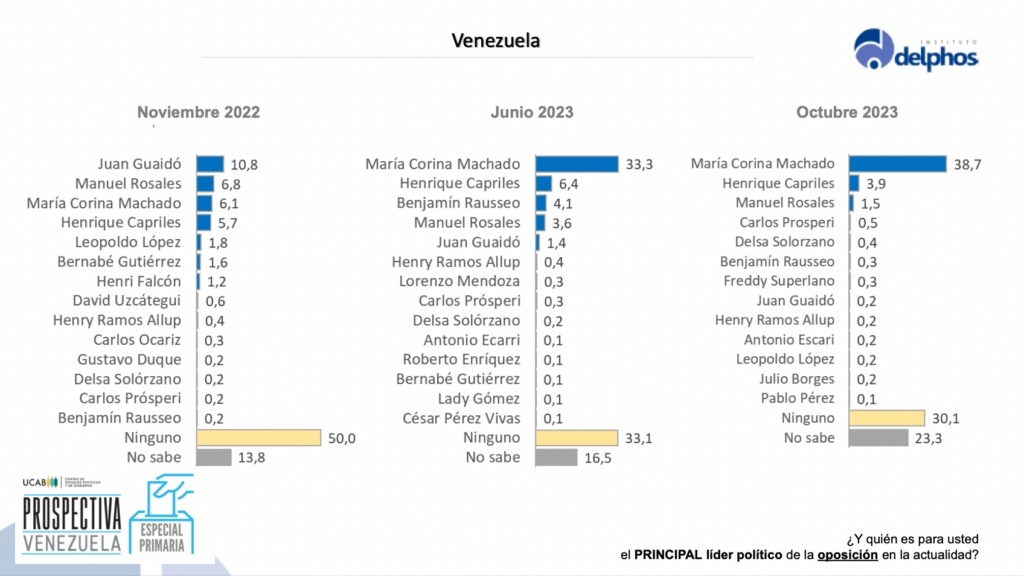

María Corina Machado has skyrocketed as the opposition voters’ preferred option. Is her rise a tacit rejection of the leadership of the G4, made up of the main opposition parties?

María Corina rises at a time when traditional leadership is badly injured. At other times, for example the 2012 primary, there were Leopoldo [López], Henrique [Capriles] and Pablo Pérez. There were three important names there. Then Leopoldo retired due to his ban from running and gave his support to Capriles. But at that time there were more names that could be contemplated by people. Currently there isn’t. The one that stuck was María Corina and there are practically no other names that compete with her at this time.

Henrique Capriles, on the other hand, is withdrawing from the primary: when he was once the favorite option of the opposition electorate. Is the opposition electorate rejecting its traditional leaders? The primary as a death sentence for the G4, which in 2015 swept away a supermajority in the National Assembly?

The primary is not a death sentence for the G4. The G4 already had a significant wound as a group. This is simply confirming a fact.

And, among the opposition candidates, Machado also ranks first among dissident Chavistas according to the survey that Delphos did for the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB). Why does a center-right, upper-class woman who promises to privatize PDVSA stand out in this sector loyal to Hugo Chávez? Beyond the discontent that Machado embodies, are Venezuelans more open to liberal or right-wing ideas, especially in economic matters?

Venezuelans are open to anything that they perceive can improve their living conditions. If the current thing has failed, that critical Chavismo begins to look outside the box to see that other things exist, beyond knowing exactly what María Corina proposes. They see her as an interesting option to observe and that is what they are doing right now: observing, seeking to see what she really is.

Capriles accused Machado of “speaking to the upper echelons.” But, according to the Delphos polls for the UCAB, Machado is the favorite opposition candidate of the lower sectors and the upper sectors. Do the popularity levels of the primary candidates vary by social sector or are their popularity levels more or less homogeneous in the different classes of the country?

They are quite homogeneous. Not at first, if we talk about February or March, María Corina stuck more in the middle and upper strata. But this has become quite horizontal, quite flat. It is an option that has won as the option that can generate the change that people want, recover their living conditions, and this has caused its name to spread throughout all social classes.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate