Fighting River Blindness in Southern Venezuela

Despite the health crisis that Venezuela has gone through, the onchocerciasis elimination program in Venezuela has continued to work reasonably well. One of its leading scientists explains why

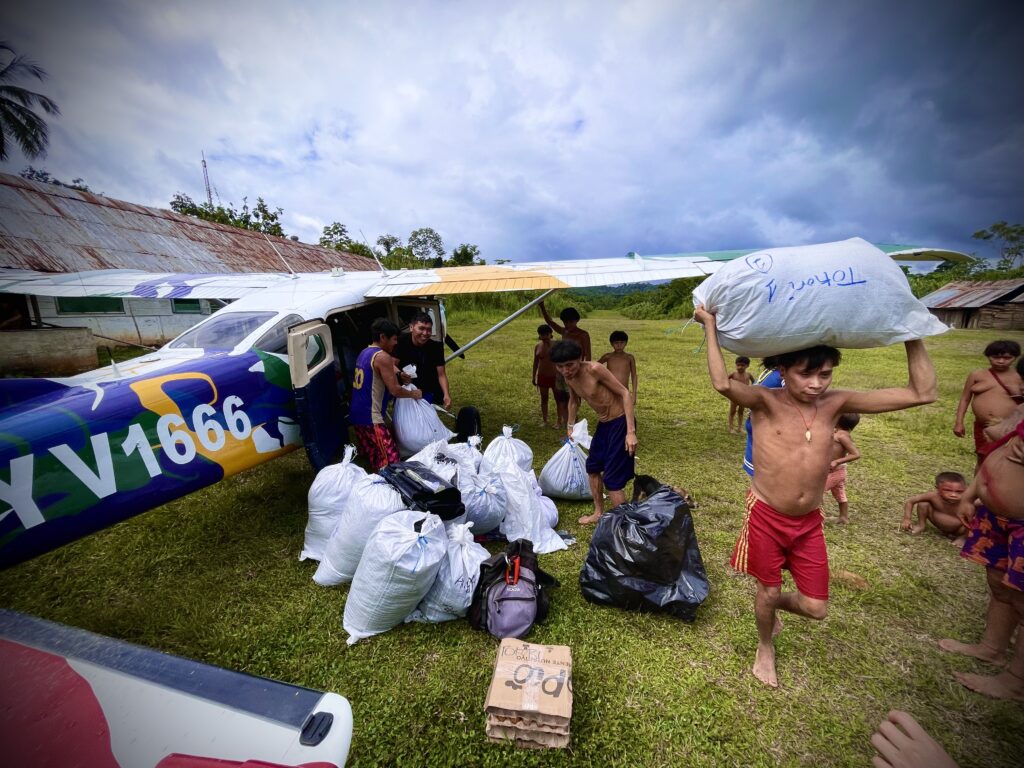

Two and up to four times a year, a team made up of health personnel from the Ministry of Health’s SACAICET (Simón Bolívar Amazon Center for Research and Control of Tropical Diseases), Indigenous Health Agents (Indigenous people trained in modern health practices) and military and civilian local personnel that give logistical support, visit around 393 indigenous communities dispersed in the jungles of the Venezuelan Amazon, in the states of Amazonas and Bolívar.

Since 2000, the health team has visited the communities –after days and weeks of crossing through the rainforest or high-altitude savannahs– to supply an antiparasitic drug called ivermectin and fight onchocerciasis: an infection caused by the Onchocerca volvulus worm. In fact, by 2016, we reported that the transmission of this infection had stopped in approximately 75% of the endemic area. Despite the health crisis that Venezuela has gone through, the onchocerciasis elimination program in Venezuela has continued to work reasonably well.

Ivermectin has contributed for more than twenty years to diminish and eventually eliminate Onchocerca volvulus, a parasite that became common in Southern Venezuela since its introduction to the Americas from West Africa during the 16th century.

This roundworm’s infectious disease –known as onchocerciasis or “river blindness”– is transmitted by the bite of the Simulium flies that breed in the mighty rivers of the Venezuelan Amazon. The infection results in skin lesions and affects the eyes, causing loss of vision and even blindness.

Globally, onchocerciasis threatens the health of about 240 million people in Africa (the continent where 99% of the cases occur) and 38,000 indigenous people between Brazil and Venezuela. Although this disease is not fatal, it can have weakening effects on the immune system, making the person more susceptible to other serious infections such as measles or malaria. In fact, the Venezuelan health teams also bring medicines, diagnostic tests and vaccines required to deliver other primary health care services to the indigenous communities, such as malaria control and immunizations.

Ivermectin has contributed for more than twenty years to diminish and eventually eliminate Onchocerca volvulus, a parasite that became common in Southern Venezuela since its introduction to the Americas from West Africa during the 16th century.

Yet, the Onchocerca parasite can be eventually eliminated through the massive and sustained administration of ivermectin, leading to a series of global and regional objectives that seek its total elimination by 2030. Indeed, this infection has already been eliminated in Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico and North-Central and Northeastern Venezuela, where there was an original population at risk of approximately 538,517 people.

In Venezuela, the disease currently affects Yanomami, Yekwana and Hoti indigenous communities from the basins of the Upper Orinoco, Upper Ventuari, Upper Siapa and Upper Caura rivers in Southern Venezuela. The Yanomami territories also include areas of Brazil, making it contiguous across the border.

The success of the health program to tackle onchocerciasis in these communities in Venezuela has been possible in part because it was conceived as a common strategy and road map to be followed by all countries under the coordination of the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA), a program financed by the Carter Center.

Yet, the program’s success is underpinned by the commitment and determination of its local Venezuelan health workers and indigenous health agents, as well as vital support from the military and local health authorities and the regional support from OEPA. This regional initiative has demonstrated that a consensus of health ministries, native communities, non-governmental organizations and public-private stakeholders –including the World Health Organization– is required to develop and implement effective and successful public health programs.

That the entire OEPA and SACAICET staff works tirelessly every day to make possible the elimination of onchocerciasis in the Yanomami territories in Venezuela has been a key element, as well as the established donation and continuous availability of ivermectin by pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co.’s Mectizan Donation Program, for all those countries that need it for as long as they need it.

This regional initiative has demonstrated that a consensus of health ministries, native communities, non-governmental organizations and public-private stakeholders –including the World Health Organization– is required to develop and implement effective and successful public health programs.

The program’s deployment in the Yanomami area in Brazil and Venezuela shows the travails it must surpass. Although only 3.15% of the remaining regional population at risk in the Americas lives there, it is a very large and geographically complex area. In Venezuela, this area represents approximately 230,000 km2, which the SACAICET-coordinated health team must travel by river (boats), land (walking, trekking and climbing), or by air (helicopters or small planes) to administer the medication regularly. In fact, access to 67% of the communities is by air, requiring several flights in small planes to transport all the necessary personnel and supplies.

The continuous challenges of this program are enormous: the remoteness and expansiveness of the Yanomami territory in the Amazon rainforest, the semi-nomadic characteristics of the indigenous population, their continuous cross-border movements between Brazil and Venezuela, among others. This has meant mapping the communities involved, incessantly searching their inhabitants when they carry out their internal migrations or cross-border movements, constructing new landing strips to board the teams and even discovering new areas not previously visited by the Venezuelan health system.

However, the achievements of this local program’s efforts in Venezuela are continuous and show that the future of communities currently affected by onchocerciasis is hopeful.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate