Why is Maduro Cracking Down on Amazonian Miners?

The Venezuelan regime –the country’s main promoter of mining– has recently launched a series of highly publicized operations against gold extraction in Cerro Yapacana. Are they working? Or is it just a propagandistic bluff?

In August 2022, the National Bolivarian Armed Force (FANB) announced two military campaigns –dubbed “Roraima” and “Autana”– to allegedly tackle illegal mining in the Venezuelan Amazon. According to the FANB, thousands of miners have been expelled from Cerro Yapacana National Park, and 471 illegal mining camps have been destroyed. Nevertheless, the true impact over the environment and mining populations remains opaque as even journalists have been temporarily arrested for crossing into the national park.

Operations “Roraima” and “Autana”, in fact, are subsets of Operation “Escudo Bolivariano 2022”, created in January of that year to tackle irregular groups –or tancol, for terroristas armados narcotraficantes colombianos in Chavista newspeak– in border states. Led by the strategic operational FANB commander Domingo Hernández Lárez, Escudo Bolivariano has executed some 112 military operations in 2023. The government claims to have dismantled almost 260 guerrilla camps in Apure and Táchira, taken over illegal airstrips south of the Lake of Maracaibo, disarticulated drug-trafficking networks in coastal states, and even arrested gangs that traffic oil infrastructure as scrap. The campaign is the most notorious example of the Maduro regime’s recent shift towards internal security, tackling criminal insurgencies from non-state actors and foreign guerrillas.

Yet, anti-corruption NGO Transparency’s local chapter has described the information regarding these operations as “scarce, opaque and confusing.” Besides the detention of some members from criminal gangs and the pictures shared on social media, Transparency says in its report, there’s little information on the groups’ dimensions, businesses, structure, geographical presence and interests. The situation pertains to Cerro Yapacana, where there’s been reports on violent fights and deaths (at least two people died and six were injured in a recent clash) and expulsion of miners, all framed in an environmentalist discourse.

Revolutionary greenwashing

When the operation was launched, Hernández Lara said it would tackle “the depredation of our forest reserves and ecocides against nature.” In December, Maduro called for the “deepening” of Operation Roraima to “defend nature and the Venezuelan ecological system.” This “environmental” focus has shone through in official propaganda where military officials attempt to co-opt some indigenous religious beliefs in order to pass-off their actions as part of a “native struggle”. References to the “Pachamama” (an Incan deity, alien to Venezuelan indigenous cultures), sacred mountains, and holy jungle are used to make it seem like counterinsurgency operations in Yapacana are actually a spiritual fight, one for the Earth itself.

And yet, illegal mining has drastically erupted in Southern Venezuela when the government created the Orinoco Mining Arc –three times the size of Panama and covering 12.2% of the country– in 2016 to lessen the impact of the Venezuelan oil industry’s collapse. The Arc led to an eruption of non-state actors which later spread towards other areas: including Cerro Yapacana national park in the State of Amazonas, where mining has been illegal since 1989.

Thus, unsurprisingly, the operations in Cerro Yapacana seem to have a propagandistic purpose. A newer phase began in December 2022, soon after a notorious Washington Post article, and AFP journalists were invited to cover anti-mining operations. In fact, Maduro seems to be seeking to join the environmental bandwagon of fellow leftwinger presidents Lula da Silva and Gustavo Petro, who have turned the protection of the Amazon into pillars of their progressive discourse, getting a lot of good press and social media support abroad. During the COP27 (2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference) in Egypt, Maduro –alongside other Amazonian presidents– called for the protection of the rainforest, the creation of a fund to mitigate the impact of climate change on the Global South and the revival of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization.

“Maduro understood that talking about the conservation of the forest, despite a terrible environmental track record, is worthy in international spaces”, says Bram Ebus, a Dutch journalist from Amazon Underworld and Crisis Group specialized in the Amazonian region. The Cerro Yapacana operation, thus, could be a sort of massive greenwashing PR strategy.

According to Cristina Burelli, founder of NGO SOS Orinoco, the government has focused on Cerro Yapacana due to the easier control provided by the rivers surrounding it –like an island– while broader areas like Canaima National Park or the Upper Orinoco are more difficult to control and “to show mediatically.” In fact, while Cerro Yapacana is shown in official media, “illegal mining has continued to expand in the Upper Orinoco, where it has grown around National Guard posts” and in places like Canaima and La Paragua, Burelli says.

“Maduro understood that talking about the conservation of the forest, despite a terrible environmental track record, is worthy in international spaces”, says Bram Ebus, a Dutch journalist specialized in the Amazonian region. The Cerro Yapacana operation, thus, could be a sort of massive greenwashing PR strategy.

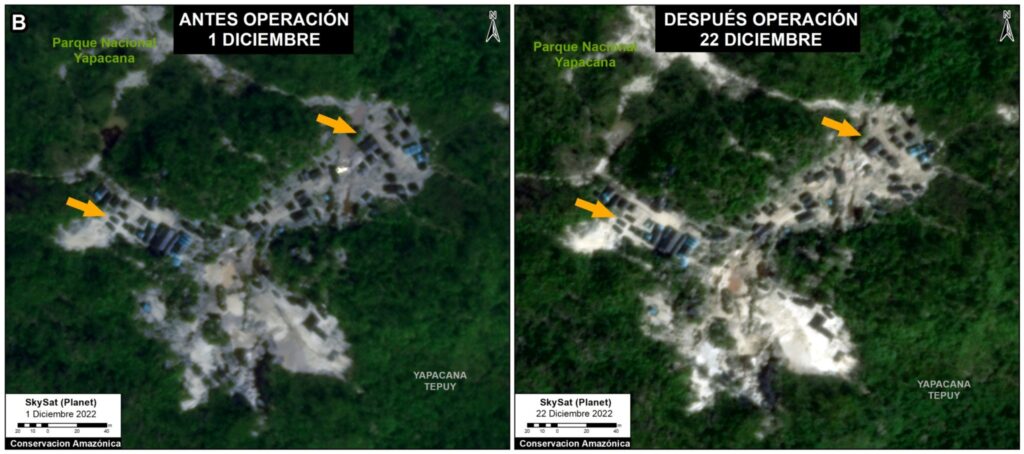

And the ecological impact could be null: according to satellite images analyzed in January by NGO Amazon Conservation, the mines on top of the Yapacana tepui remained intact after the December military operations. It’s even possible that operations in the region may be making things worse for the wildlife, seeing as the army’s preferred method of “dismantling” mining camps is to just burn them all down. Likewise, official channels have published videos showing soldiers detonating mining barges on waterways, as well as images of oil drums used to house dangerous chemicals being set alight in mass pits, reminiscent of the controversial burn pits which may be to blame for serious health conditions faced by US troops after the Gulf War and 2003 Invasion of Iraq.

“We don’t know whether the engines, pumps, fuel, etc. [of the detonated mining barges] had first been dismantled. And, of course, if mercury was transported and used in them”, says Alejandro Álvarez Iragorry, general coordinator of environmentalist NGO Clima21, “in any case, they could’ve brought them to land to be dismantled so as not to continue accumulating metal and other types of waste at the bottom of the rivers.” Álvarez Iragorry believes it’s likely the barges had no mercury when they were exploded, as it is an expensive metal, but reports of confiscated mercury (which is illegal in Venezuela) are scarce. “They aren’t working with experts”, Burelli says, “they haven’t included civil society, indigenous groups and academic experts that need to participate in reforestation projects.”

According to Burelli, if the government truly wanted to halt illegal mining south of the Orinoco, it could stop miners’ access to protected areas, halt the Venezuelan Corporation of Guayana’s fuel supply to the mines and crack down on the widely generalized but illegal trafficking of mercury.

The end of Amazonian feudalism

In fact, the government could have an interest not in eliminating the mines but in taking direct control of them and its revenue from non-state actors. According to Burelli, sources in Cerro Yapacana told SOS Orinoco that mining continues in the area despite the displacements, and control of the mines have been transferred from armed groups to the FANB. “A thermometer to measure this is the economic activity of Inírida” in Colombia, Burelli says, which functions as a sort of “financial center” for the gold trafficked from Cerro Yapacana. Yet, according to Burelli, sources in Inirída say that “until quite recently” its economic activity hadn’t changed.

According to Ebus, the government sought to gain from the revenues Venezuelan gold is generating in Colombia. “We’ve even heard of the military getting mining machines inside [Yapacana] the same week the operations happened”, he says.

In 2021, NGO Clima21 reported a possible decrease in Venezuela’s deforestation rate that could be related to the state’s new policy of expelling informal miners from mining areas in the Orinoco Mining Arc while handling concessions through “strategic partnerships” to bigger private companies. The State also led security operations last year against the Las 3R gang in Tumeremo, a mining town in Bolívar, which also shows its drive to have more control over the Orinoco Mining Arc. In fact, the spectacular military operations in Tumeremo and Imataca resulted in the militarization of the area, the takeover of mines and equipment, and –according to local newspaper Correo del Caroní– the displacement of over 1,000 miners.

It’s incredibly difficult to measure the real strategic gains brought about by military operations in the Venezuelan Amazon. FANB officials’ press releases include the number of alleged mining camps that have been torn down, the alleged number of miners that have been arrested or forcibly removed from where they worked and even include pictures of Colombian military uniforms and random collections of shotguns and rifles in varying conditions. Yet, context is usually completely withheld.

One scroll through Hernández Lara’s Twitter profile is enough to find tens of videos of alleged illegal miners holding up signs to display their personal information, appearing to confess to crimes on camera. Coincidentally, many of them happen to be Colombian. While it’s true that Colombian paramilitary groups have been operating for years in Venezuela, it’s been impressive to watch as official propaganda paints a picture that can be used to easily blame all internal security issues on foreigners. For propaganda purposes, Colombians are a fantastic scapegoat for all local security failings as well as some great cover for shady power struggles.

According to Hernández Lara, more than 11,500 illegal miners had been expelled from Yapacana by early September. Of course, there’s no way to verify these numbers but Colombia’s Ombudsman’s Office alerted in June that the Colombian departments of Vichada and Guainía could end up receiving 7,000 Colombian miners expelled from Yapacana. Nevertheless, the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office has only recently reported the arrival of 114 people, including 105 Venezuelans. Where are the other thousands going to, if they are actually being expelled?

In any case, the recent operations have been used to rile up some patriotic fervor for the Armed Force, a move that probably holds some good propaganda value for the 2024 presidential elections. Just recently, on the CEOFANB’s 18th anniversary, Nicolás Maduro decided to dress up in uniform and LARP around the Defense Ministry in a meeting with Hernández Lara and other high-level officials. That meeting featured all the relevant parties inside a field tent, with the tables everyone was sitting at covered in camo netting… inside the Defense Ministry in Caracas. If anything, it provides valuable insight into how Maduro just sees all of this as a propaganda opportunity to present himself as the embattled man of the people who fights the foreign intruders and saves the planet by detonating barges on rivers.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate