What is Venezuela Actually Seeking With the Esequibo Referendum?

Venezuela’s authoritarian regime is holding a referendum over a claim the country has kept for decades. Why? To face the opposition, measure its mobilization power and stroke electoral nationalism before the 2024 elections

The Guyana-controlled Esequibo region, claimed by Venezuela for more than a century and formally disputed again since 1966, is tacitly included in Article 10 of the Venezuelan Constitution which says Venezuela’s territory follows the borders of the colonial Capitanía General de Venezuela and subsequent “non-vitiated” arbitral awards (Venezuela’s official claim over the Esequibo says the territory was a part of the Capitanía. The country also considers that the 1899 Paris Arbitral Award, which officially handed the Esequibo to Great Britain, is “null and void”). The case at the International Court of Justice has been ongoing since at least 2018 –following diplomatic escalations after Guyana handed offshore concessions to Exxon Mobil and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation. So, why is Venezuela now organizing a five-question referendum –an electoral act that will not dictate the decisions of a militarist-authoritarian regime– on its claimed sovereignty over the Esequibo? There might be three reasons:

A response to the opposition primaries

The referendum is a show of strength to the unexpectedly high participation in the opposition primaries (2.3 million in Venezuela). Maduro has already affirmed that around 3.5 million people participated in the Esequibo referendum drill on November 19th, but the National Electoral Council didn’t publish official results. In fact, while it happened when Guyana handed new oil concessions, the referendum was announced by the Chavista-controlled 2020 National Assembly barely a month before the primaries: when María Corina Machado’s skyrocketing rise was already clear as crystal and the final version of the Barbados agreement was being reached upon.

This approach is clearer in PSUV’s Héctor Rodríguez’s recent statements: “the queues of voters for the mock referendum for the Esequibo were very much longer than the ones in the opposition’s primaries, impressive. The primary does not exist, it was nothing.”

It’s not the first time such a retaliatory display of political muscle takes place. During the 2017 protests, more than 7.6 million people allegedly voted in a self-managed referendum organized by the then opposition-controlled National Assembly to reject the creation of a National Constituent Assembly (ANC). A few days later, Chavismo announced that more than 8 million voted to choose the members of the ANC. The results were denounced as fraudulent, with at least an extra million votes, by software company Smartmatic – which provided the voting machines.

The referendum has already stoked divisions within the opposition. While Machado has called for its suspension, Andrés Caleca has announced he will participate and Henrique Capriles has even promoted it. The Unitary Platform, meanwhile, said that each voter should decide what to vote and if to vote.

Mobilizing Chavistaworld

Chavismo is also seeking to measure its mobilization power in its bases and clientelist networks before the 2024 presidential elections. Chavismo, for example, barely managed to mobilize 3.5 million people in the last regional elections – 2.3 million less than in the 2017 regional elections. The opposition, instead, gathered 100,000 more people in the primaries than the Democratic Unity Roundtable did in the 2021 regional elections.

An example of this mobilization “experiment” is the creation of “Patrol Chiefs” in the National Guard to deploy a 1×10 plan, an old Chavista strategy in which each official must take 10 family members or close friends to vote. The plan was first deployed in the November 19 drill. Similarly, the government announced Communal Councils, the National Militia, the recently created Congress of the New Era and CLAP committees –all part of its clientelist networks and bases– will join ruling party PSUV in the “5×5” strategy to supposedly mobilize the outrageous number of 12 million voters.

This strategy has led to claims of local committees menacing to CLAP food bags away from beneficiaries that won’t vote in the referendum and in an express operation to print IDs (necessary to vote) that has resulted in chaos to some SAIME offices.

Suspending the elections?

While this is still in the realm of the speculative, there is the possibility that Chavismo is seeking to create a climate of war or confrontation to decree a state of emergency and suspend the 2024 presidential elections that –if they are moderately competitive, following the Barbados agreements– could be catastrophic for PSUV. The strategy could be a toned-down version of Argentine dictator Leopoldo Galtieri’s 1982 Falklands War, when the Argentina junta disastrously invaded the disputed British-controlled Malvinas islands to raise nationalist sentiments and mitigate its domestic unpopularity. While a war could blow the sanctions relief, it’s clear Chavismo prioritizes keeping power over ending sanctions.

Frontal warmongering is still low in the dispute, but the Venezuelan Armed Force announced is building airstrips and civilian buildings near the Esequibo, while one of the referendum questions included proclaiming the region as an official Venezuelan state and handing Venezuela IDs to locals. Meanwhile, Guyana met with Brazil in its 26th Annual Regional Military Exchange Meeting, where Brazilian Brigadier General Paulo Santa Barba said that a problem that “affects one country could have repercussions for everyone.” Brazil, which has economic interests in the disputed region, has in fact strengthened its defense in the border region in the last few days.

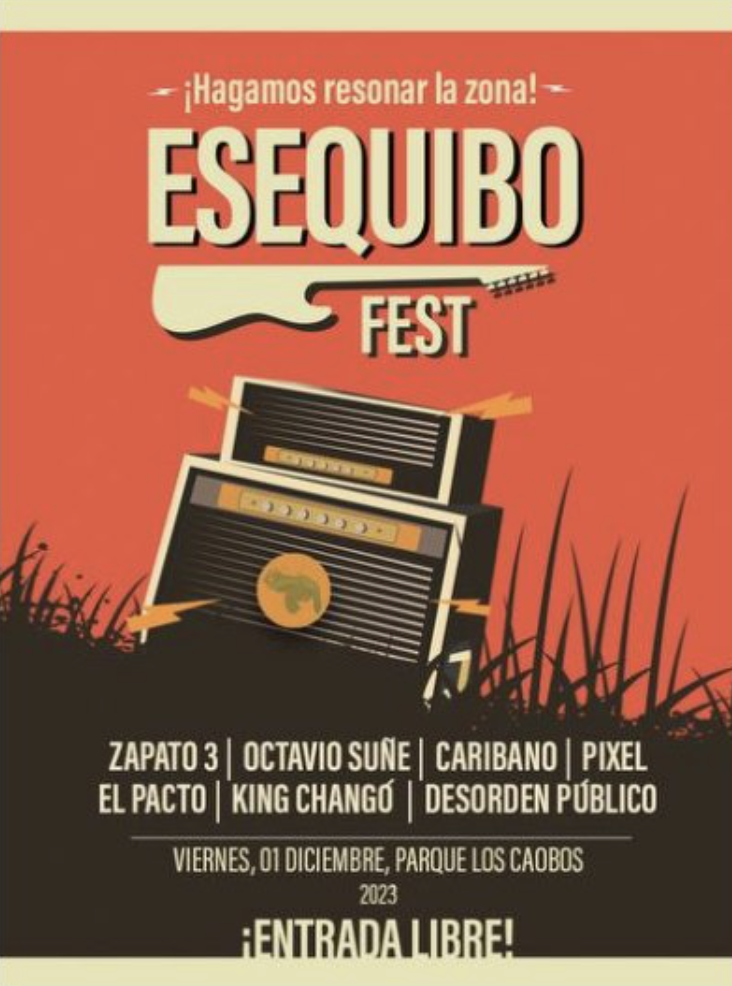

So, if Argentina’s 1982 war had a festival for the Falklands as a prelude and Venezuela is now organizing the Esequibo Fest, what assures us that the similarities between Galtieri’s and the Maduro regime will end there?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate