Memory-Holing The Chataing Era

The Bolivarian revolution, in all effect, is a revolution. The almost unnoticed passing of Gustavo Cisneros and the erasure of cultural products of the Chataing Era show the extent of Chavismo's impact in our collective memory.

Gustavo Cisneros—the Venezuelan media mogul, a one time billionaire, who owned one of the largest Spanish-language media groups in the world and the once almost-dominant Venezuelan television channel Venevisión—died a few weeks ago. It was shocking to see how little relevant that news was. Beyond the accusations against the business tycoon, who some loosely blamed on Twitter as being responsible for Chavismo, the response of the majority was really one of indifference.

The response to Cisneros’ death is evidence that Chavismo was able to make a complete and successful revolution: when one order replaced another and created a new status quo to the point that those who oppose the ruling elite do so using the laws, norms, and cultural codes of those who started the revolution. That is, they oppose Chavismo as a political movement, but they do so within its conceptual framework and using their cultural codes.

In this sense, and contrary to what some irresponsible analysts claim, the Bolivarian revolution is—in all effect—a revolution. The history prior to its existence, the values prior to its imposed order, are increasingly diffuse in the memory of few.

If we wanted to talk to someone who was a functional adult in the eighties, when Saudi Venezuela was dying, we would have to go talk to a person already entering their old age. And if we wanted to ask someone what a stable and prosperous Venezuela was like in the seventies, it would be impossible to do so with someone under… seventy years old?

It is impossible for this generational change not to have cultural effects. Does anyone know that the person who died is one of the most important and influential businessmen of the entire Venezuelan 20th century? Cisneros’ death should have been the equivalent of Carlos Slim or Ricardo Salinas dying in Mexico.

But no. At the time I write these lines, in January 2024, a search on Twitter reveals that, a couple of weeks after his death, he is only mentioned in a few insulting tweets and a few institutional publications from Venevisión. In fact, it was in the Dominican Republic, where Congress paid him a tribute.

A Neuralyzer For Venezuela’s Late 1990s

This is not a nostalgic article. It’s not an article about nostalgia either. It is, in fact, an article about revolutions, about a particular revolution, about oblivion. It is not about lost youth, but about erased youth; forgetfulness, the little red flash of the Men In Black eliminating your memories and implanting others.

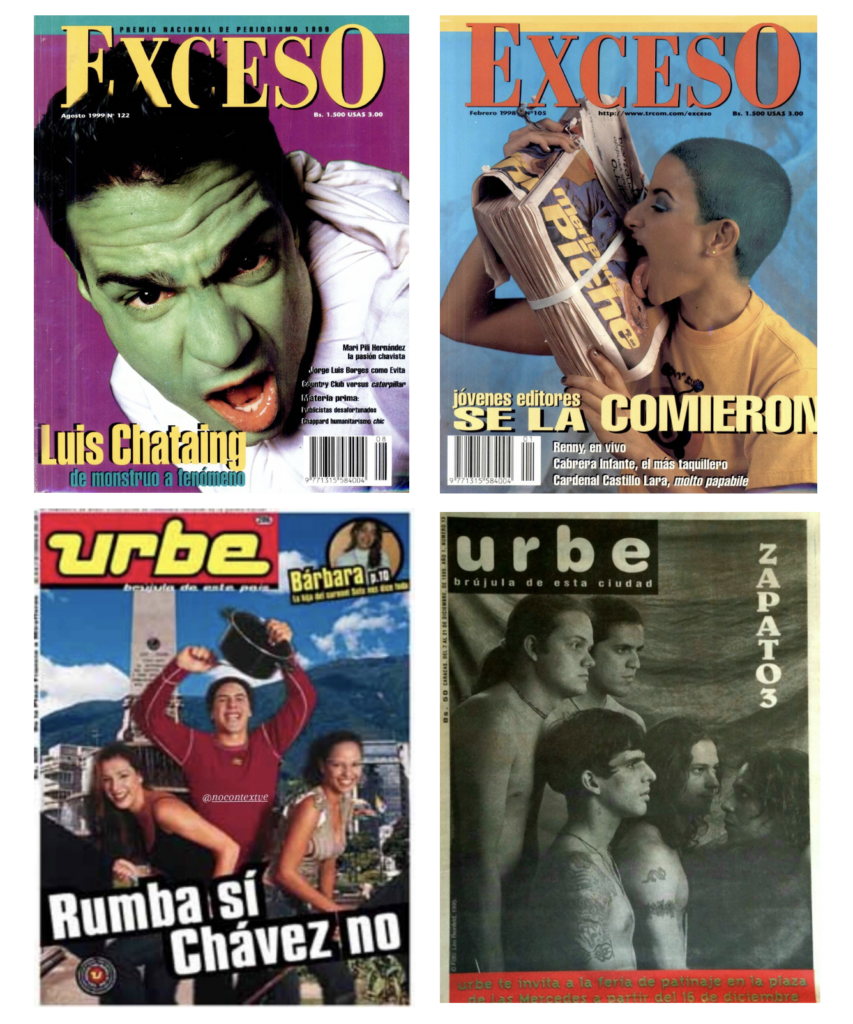

All these reflections arose from the video “Fe de Erratas: Luis Chataing [y qué puede aprender de Danny de Vito]”, from Hammerspace Podcast. In that episode, host Cristian Caroli takes a look at Luis Chataing’s career, his fall and the hatred that the character arouses today.

Watching it, I wondered if people understood who Chataing was and what it meant to my generation. Contrary to what some might think, Luis Chataing was one of the most original, interesting, disruptive, and talented mass communication figures of the 1990s.

His brand of t-shirts, his radio program, his jump to television, the breaking of communication patterns and taboos, his irreverence and the use of humor that was not common in the local scene, made Chataing a referential and very influential figure in Venezuela.

At a time when assimilating foreign alternative influences (mainly North American) was not as easy as it is today thanks to the Internet, Chataing was part of an alternative and irreverent country that reared the youth of the time. Along with him: the Urbe newspaper, its director Adriana Lozana and its writer Eric Colón, Gabriel Torrelles, Alejandro Rebolledo and Henrique Do Couto; the Festival Nuevas Bandas, the Miércoles Alternativos, Cayayo, DJ 13, the rap battles in Los Próceres, the graffiti artists, Neutroni clothes, the music store Esperanto, that fat guy that had a used CDs store in Chacaito, nightclubs like The Flower or The Doors, Félix Allueva, TV host Stayfree, la Belle Epoque, the Caracas rock bands’ circuit, newspapers like La Merma Impresa, the CCCT punks, photographer Fran Beaufrand, DJ and visual artist Muu Blanco, DJ Tony Escobar, radio shows like El Show de la Gente Bella, Rockadencia, El Show de la Mañana and Zona Radical; the rockers from Mérida who were accused of being part of a Satanic sect, the raves, radio hosts like Ely Bravo and el gato Guillermo Tell, the HIV awareness spots from the Daniela Chappard Foundation, Exceso magazine…

That country, by the way, had enemies. Because we were young and irreverent and we had to hate someone. So we hated Gustavo Pierralt, because he said “thank you for existing” to those who made live calls to his show. If you admired Chataing you hated Daniel Sarcos. If you liked Urbe you hated a youth magazine that circulated around the UCV and about which I don’t remember anything. In the radio show Rockadencia, hosts Gustavo Zambrano and Fernando Ces broke the first DespuesDeVieja album because Ramón Castro, their guitarist, had starred in a RCTV teen telenovela and they didn’t forgive him for it. And Metro Zurdivision hated Los Amigos Invisibles, and so on.

Nostalgia and forgetting are part of life. If you can forget your youthful loves and suicidal dalliances, how can you not forget a little punk band called La Puta Eléctrica?

But Venezuela’s case is not oblivion or nostalgic thirtysomethings wanting to return to a country where everyone has already grown old. No, here we are talking about a new established order and a stolen old order. And there seems to be no record of that country.

In the case of Chataing, what motivated Cristian’s video is Chataing’s Masterclass, in which he covers his entire career as a personality interview over the course of just under two hours and twenty minutes, and the interview that Chataing gave to Oswaldo Graziani in his podcast “Chiste Interno” where they talked about the main items of his career.

The masterclass as a recounting of an era is tremendous. There, Chataing tells us – through the milestones of his career– about a form of communication and media that disappeared. But it was not technology and the passage of time that destroyed them, but a cultural tsunami called Chavismo.

It was Chavismo that eliminated radio stations in Venezuela; the rebellious 92.9 FM (and eliminated all uncomfortable content from its rival La Mega Estación). It was Chavismo that led the apolitical Chataing to get into politics. And not only him, but the entire artistic-media showbiz of the middle class, which was defeated and forgotten shortly after.

Listening to Chataing is then a journey. Something like watching the documentary that Gustavo Cisneros had himself made a few months before he died. Both products may be tailored to the ego of their producers, but you know that the recounting—which safeguards a memory—is worth it.

Cisneros was a visionary and brilliant businessman who knew how to see market niches that no one saw before him, that his business moves are among the most sagacious in the country’s business history and that his most influential company reflects Venezuelan idiosyncrasy. And yes, that may scare some who see in Venevisión, its aesthetics and content a condensed sample of the worst cultural evils of Venezuela.

On the other hand, one witnesses the rise of a communicator who broke paradigms like few others in his time, the typical outsider who took an ancient mass media form by storm and knew how to modernize it, break it and impose trends on it.

But the answer doesn’t reflect that. On the other hand, it shows a kind of shame on the part of the oppositional middle class to recognize itself in that past. “Chataing is a talentless idiot who only influenced mediocre comedians,” they say on networks with somewhat unfair simplism. As unfair as giving Gustavo Cisneros the responsibility of Chavista consolidation, as if Cisneros were to blame for the fact that most Venezuelans saw in a talkative and resentful coup plotter the solution to Venezuela’s democratic exhaustion.

I won’t go into psychological gunfire here, but I think there is a lot of poorly assimilated trauma in that unbridled hatred that from time to time we unload on anyone who was an opposition figure during some stage of Chavismo.

The Venezuelans who lived glued to Venevisión during the 2003 strike, waiting for Napoleón Bravo or Anna Vacarella to tell them what to think, are the ones who today hate Cisneros and accuse him of being a “traitor.” The Venezuelans who believed that Nacho, the reggaeton singer, was a brilliant and lucid young man in 2016, are the ones who today echo his showbiz gossip and applaud those pathetic videos where the singer tantrums over a joke. And the same people who four years ago believed that Juan Guaidó was the reincarnation of Churchill are who today accuse him of being a bon vivant paddle tennis player.

White hopes

But as a song by Caramelos de Cianuro says, which precisely talks about youthful nostalgia: “I know, that wasn’t that long ago; I lived it, they didn’t tell it to me.”

So, I remember when the country loved Venevisión. I was at a rally in 2003, when the tiger mascot from the channel got up on a platform to dance and the ladies below went crazy. As crazy as when Chataing arrived at the rallies and everyone applauded him.

In those days, Chataing publicly reconciled with Daniel Sarcos. That was a sign of “unity,” which people demanded in the face of Chavista hatred and division. And then, when he toured the country with his television program taken off the air by Conatel, I remember that middle class that filled his shows and shouted at him to “jump into” politics.

I remember the ladies who loved Nacho, Fabiola Colmenares, Ramos Allup, Leopoldo, Guaidó—and Chataing and Cisneros, and now María Corina Machado—and anyone else who looked like they knew how to read and write, who represented the anti-Chavismo. And I remember the passion with which they were loved and idolized which was the same with which they were stoned and sent to oblivion.

In Venezuela we have turned these figures into white hopes against Chavismo. One day we think they are great, and we hope for them. Shortly after, we became disappointed because “they did not overthrow Chavismo,” and we accused them of being traitors.

The best way to get rid of them? The same as the scorned man who is dumped and becomes an Andrew Tate fan, saying all women are “hypergamous”. The two sides of the same coin: disappointment, sadness for what was lost, spite for a failure that one cannot assimilate. And most importantly: the vision of one’s own responsibilities in the disaster.

Will the same thing happen now with María Corina Machado, the new repository of our hopes? I hope not.

On the other hand, just as the best thing when ending a relationship is to assume one’s responsibilities and take note of the lessons to be able to face the next courtship, in Venezuela it would be better for us to stop demonizing those anti-Chavistas who failed and learn from the mistakes they made. But it is more comfortable to wash our hands and drain our guilt by throwing stones. Thus, what an irony, we contributed to the revolution and its need to make us forget everything that existed before it.

It is worth saying that I believe that cultural products such as the “Free Cover” music sessions, the Cusica Fest, Diego Vicentini’s film “Simón” or the podcast “Venezolanos” by Rafael Arráiz Lucca point in a good direction: one that does not give in to excessive idealization of the past, as nostalgic people do, but also not to the rabid tantrum of those who try to forget everything so as not to remember their failures.

However, I think it is appropriate to reconstruct the history of our democracy and the country where we grew up. It is necessary to revisit recent milestones: 2002, the recall referendum and the cultural life of the first years of Chavismo—all those things that accompanied us until we got here. And to do it without victimhood, without the cry of “betrayed people,” with which we always tell ourselves our own story.

At least, so be it for historiography. To record what was destroyed.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate