How Chavismo Neutered The Strength of 1990s Venezuelan Activism

The Chavez and Maduro governments co-opted activists and destroyed the conditions for the activism that partly helped them to rise

Last February 27th, on another anniversary of El Caracazo –a series of massive looting and riots that battered Caracas in February of 1989 and resulted in hundreds of deaths– the discussion reappeared as to why similar situations did not occur in Venezuela during the worst years of the crisis and under a complex humanitarian emergency. The answer relies on Chavismo taking into account the variable of a possible repetition of the events of February 1989, despite the presence of the “objective conditions” that caused the looting. Just as it learned from April 11th, 2002 and the 2017 protests, Miraflores has cut off the set of associative ties that made the expression of the crowds’ indignation possible.

In the case of “El Caracazo”, we will repeat ideas from the “Environmental Rights Yesterday and Today” forum, held on November 18 at the Casa Disiente in Caracas, where activists Claudia Rodríguez, Jorge Padrón and Liliana Buitrago made a historical assessment of the environmental movement in Venezuela. Although it may not seem like it today, in the 1990s the environmental movement had a presence in almost the entire country, demonstrating an important capacity for mobilization and advocacy with the authorities.

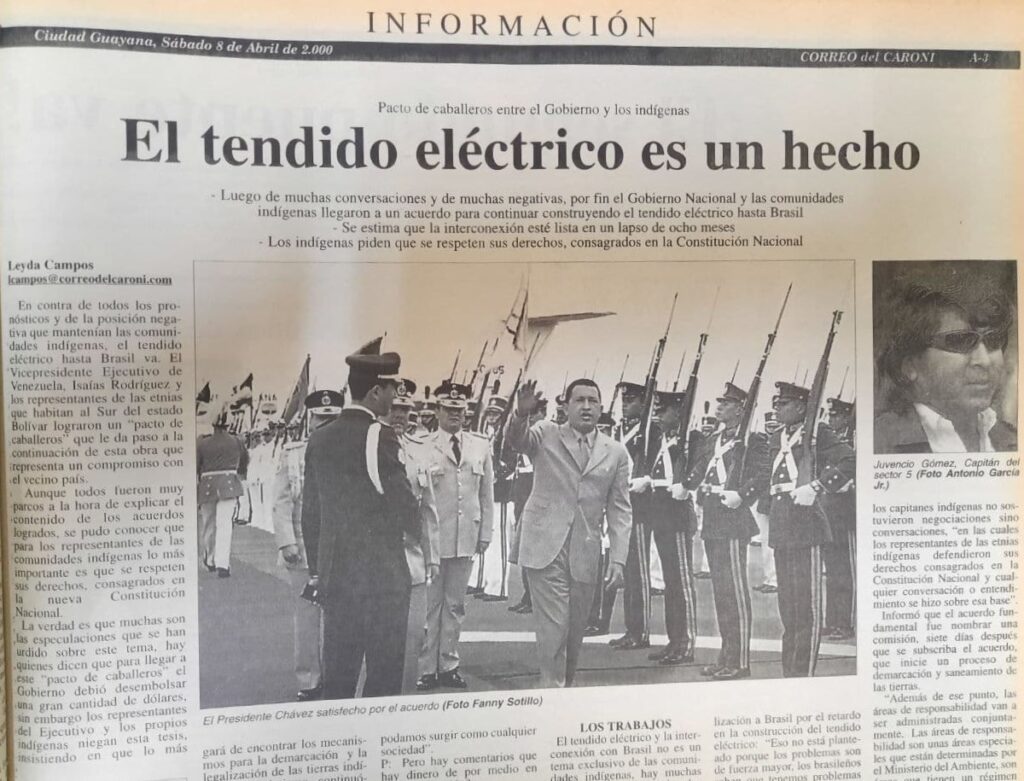

As the debate recalled, in 1997 Venezuelan environmentalists managed to generate sufficient critical mass to reverse the so-called 1850 Decree, which allowed extractive activity in the Imataca Forest Reserve in the states of Bolívar and Delta Amacuro. An emerging Bolivarianism, in the form of a political-electoral movement, capitalized on citizen demands in its favor – assimilating a good part of those green activists of the 90s. But State co-option had the objective of neutralizing society’s autonomous capacity for mobilization and struggle, including environmentalism. The takedown of transmission towers by indigenous people in Brazil in the year 2000 was the last wind of independence of Venezuelan environmentalism.

In 2004, Hugo Chávez issued presidential decree 3.110, which once again allowed mining and logging exploitation in Imataca. And the decision, at the height of the Sabaneta leftist’s popularity, occurred without any social response. The combative greens of yesteryear were already part of the new establishment. However, the transformation of environmental rights defenders into officials is insufficient to explain this appeasement. This was accompanied by a deliberate policy to end the material conditions that supported and made this type of activism possible.

The first of these decisions was to bend the country’s public university network. Analyses of Chavismo’s confrontation with higher education institutions have tended to explain it by the cornering of academic freedom and the generation of knowledge, which is true. However, a dimension that is omitted is that the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) and similar universities were a key territory of operation not only for leftist organizations, but for all the associative and union expressions that appeared in the country since the late 70s.

The infrastructure of the university, for a long time, was key to the emergence and expansion of demands of all kinds. Its classrooms and auditoriums hosted regular meetings and regional and national meetings of various kinds, with zero cost for their promoters; university canteens provided the catering during those days; its buses guaranteed mobilization, both in the city and to different parts of the country; university printers duplicated proclamations and manifestos, in offset or in rudimentary multigraphs; professors and students processed the data that fed the narrative of the demands.

Ending the university, also, was a way to eliminate the material substrate used by the country’s social and popular organizations. If the metaphor is valid, it is as if a political party with broad reach had all of its national headquarters raided and confiscated at the same time. Its operational capacity will be considerably reduced.

A second dimension of the characteristic activism of the 1980s and 1990s, which ultimately brought Hugo Chávez to power, is that it was based largely on volunteerism. Unlike the scheme possible through international cooperation, which developed around the world at the end of the 90s, in those years the different and emerging neighborhood, student, indigenous and countercultural movements were based on voluntary effort and altruistic mutual support.

People received a salary sufficient for their basic needs, so they had the possibility of dedicating their free time to, and even financing out of their own pockets, the citizen initiatives in which they were involved. With the purchasing power of the salary dynamited, placing all people in the Darwinian struggle for survival, there is no time, desire or economic possibilities to transform reality through an associative effort.

A third and final dimension, which I add from my own perspective, is the breakdown of horizontal community ties in low-income sectors. When the government knew of the looming economic crisis in 2014, after the significant drop in international prices of its main export products, it made two decisions. The first was to create the counter-narrative of the “economic war”, blaming businessmen and the private sector, to explain all the evils that the majorities were going to suffer next. And in parallel, carry out the largest police-military intervention operation in the country’s barrios: The People’s Liberation Operation (OLP), which over time would be replaced by the Special Action Forces (FAES).

After the 2002 coup d’état, Chavismo carried out the necessary purges and restructuring within the Armed Force to prevent something similar from happening in the future. The same can be said of the protests of 2017. If El Caracazo cannot be repeated after 25 years of Chavismo, despite the impoverishment and marginalization of the majorities, it is because the ruling party has taken measures to destroy the social ties that made it possible.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate