A Brief History of How Chavismo Destroyed Trust in Elections

Chavismo promoted participation at the height of Hugo Chávez’s popularity, before turning into a massive barrier to electoral rights. The patterns they developed are still in place

With Venezuela headed to presidential elections on July 28th, it’s hard to imagine what it means to have appropriate electoral conditions in Venezuela. The erosion of Venezuelan elections through the lens of the decrease in electoral trust shows how Chavismo evolved from a champion of voter participation to erode the electoral system through the disenfranchisement of millions of voters.

It might be difficult to understand in 2024, but Chavismo used to be quite friendly to elections when it counted with a sizable popular support. President Hugo Chávez had two commanding victories in the 1998 and 2000 presidential elections, winning by 56% and 59% of the vote respectively. During the early years of his presidency, there were efforts to increase voter participation. According to an OAS report, in 2003, 7 out of 10 Venezuelans did not have a cédula de identidad (identity document). In response to this, in 2004, the Chávez government created the Misión Identidad, a social project that would issue those ID documents, which, in turn, led to a 34.5% increase in voters in the Permanent Electoral Registry (REP).

The growth of the electorate occurred simultaneously with an emerging sense of distrust in the country’s elections. This started in 1999, when the government’s call for a Constituent Assembly excluded the proportional representation system in favor of a majoritary one that was combined with a government campaign strategy called “Kino” after the popular lottery game. This system resulted in Chavismo winning 93% of the seats despite attaining only 53% of the vote, effectively handing it control over the rewriting of the Constitution and the reset of all institutions.

These attempts to game the election quickly transformed procedural irregularities, especially with the appointing of officials to the National Electoral Council (CNE). In 2003, the National Assembly –which is constitutionally responsible for naming the rectors– was sidelined by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice. The latter designated pro-government officials to be in charge of organizing the 2004 recall referendum against Hugo Chávez. The feeling of distrust spread throughout the opposition led to its poor performance both in the 2004 referendum and the regional elections that occurred later that year, where they were able to only win 2 out of 23 states.

There was never any irrefutable proof of that fraud, and the integrity of the electoral system was backed up by both national and international observers. Yet, the widespread concerns about electoral integrity led to the massive dropout of opposition candidates just mere days before the 2005 parliamentary elections.

Moreover, Venezuela continued its transition to an electronic electoral system, a process which had started in 1993. The opposition coalition of the time, the Coordinadora Democrática, complained about electronic electoral fraud in their defeat in the 2004 referendum. There was never any irrefutable proof of that fraud, and the integrity of the electoral system was backed up by both national and international observers. Yet, the widespread concerns about electoral integrity led to the massive dropout of opposition candidates just mere days before the 2005 parliamentary elections.

However, trust was moderately regained in 2006 when, in the Chavista-controlled National Assembly, some opposition voices were able to enter the CNE. This helped mobilize some of the turnout in that year’s presidential elections, as many in the opposition started to once again consider voting as a useful mechanism for political change, even if the opposition’s candidate, Manuel Rosales, was defeated.

However, trust in an electoral system is more than confidence in the technical mechanisms that conduct elections. It’s the trust that those results will matter and have an impact on political life. Precisely what was wiped out in the following years eroded by the government’s dismissal of election results.

For instance, in 2007, the government’s defeat in the constitutional referendum was fully disregarded. Most of the government’s proposals the majority voted against in the referendum were later enacted by President Chávez through an Enabling law. The following year, the competencies and financial capabilities of the Mayor of Caracas were significantly reduced once Antonio Ledezma, the opposition’s candidate, won the election. Later on, in the 2010 parliamentary elections, the CNE’s gerrymandering efforts also resulted in a National Assembly where Chavismo held a majority of the seats despite only getting 48.1% of the national vote. These developments created the sense that, even if the government were to lose an election, it would be quite difficult for that to have a tangible impact on the country.

In the following presidential cycle, the 2012 election cycle, there were massive complaints about uneven campaign conditions. The government used the full force of the state for Chavez’s third re-election campaign against Miranda governor Henrique Capriles Radonski, using social programs like the Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela to promise over a million houses, campaigning on obligatory TV and radio transmissions, and using government resources for campaign events.

These actions received virtually no pushback from the CNE, who even moved the presidential election from its traditional December date to October, seemingly to accommodate Chávez’s worsening health condition, all of this hurting the principles of impartiality that are vital for trustworthy elections. Furthermore, there were concerns about the quality of the electoral registry. While UCAB’s Proyecto Monitor Electoral found that its growth matched demographic changes happening in the country, there were multiple complaints about the presence of deceased voters in the registry, which did not receive regular updates during the previous years, furthering the notion that the electoral system was tilted in favor of the government, and that it was not transparent with its process to skew the results.

The trends of worsening transparency and impartiality accelerated after Chávez’s death during the 2013 presidential cycle when Chavez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro, ran against Capriles. Once again, a sizable amount of government resources and airspace were used in the service of Maduro’s campaign and the election date was set barely a month after Chavez’s death with minimal campaign time. Then, the CNE announced that Maduro had won the election by almost 1.5% of the vote, and the TSJ declared as inadmissible the multiple complaints of electoral irregularities.

In the following years, the government continued pushing electoral dates in its favor, using government resources for campaigns, and severely limiting the capabilities of the offices won by the opposition and naming parallel officials to execute their functions. For instance, Elías Jaua was named Protector of the state of Miranda once he lost the 2012 gubernatorial election. Likewise, Antonio Álvarez was Protector of Petare and Ernesto Villegas as Minister for the Transformation of Caracas, when they lost their respective elections in 2013.

The most notable of that pattern of creating parallel offices happened when the opposition, in 2015, won a majority at the National Assembly, despite sizable attempts to sway the election in favor of the government, which included the disproportionate establishment of voter registration efforts and voting centers in government strongholds and even the takeover of the political party MinUnidad, whose name and imagery resembled those of the opposition coalition MUD, to confuse voters.

After multiple judicial obstructions, in 2016, the TSJ ruled that the National Assembly was “in contempt” and, as it did with the Mayorship of Caracas, blocked most of its functions. Moreover, in the following year, it created a parallel alternative to the National Assembly: the National Constitutional Assembly. The much-decried election for this parallel legislature did not include any opposition participation and happened amidst the violent crackdown against the 2017 protests. After its results, it even led Smartmatic, the company in charge of election machinery, to denounce that the results had been inflated by over a million voters.

The election of the National Constituent Assembly concluded the little trust in the electoral system that was left after over 10 years of unaddressed transparency concerns and incremental impartiality. Its establishment solidified the belief that elections in Venezuela were not a plausible mechanism of change. However, it was not the only transformation facing the electoral system because, throughout this time, the government became increasingly hostile towards opposition participation. Just the year before, the CNE had dismissed Henrique Capriles’ referendum proposal for the removal of President Maduro despite having fulfilled all procedural steps.

As the 2018 election approached, opposition parties like Primero Justicia (PJ), Voluntad Popular (VP), Partido Unión y Entendimiento (Puente) were barred with an unusual legal mechanism started by the National Constitutional Assembly and, most importantly, the electoral registry was open for new voter registration only for 10 days, as opposed to the usual months-long process, and deployed only 531 voting registration sites, which indicates an active effort towards voter disenfranchisement. Despite having a significantly higher daily average of registrations in comparison to 2015, there were only 807,905 new voters registered, according to the NGO Observatorio Electoral Venezolano. This left, potentially, millions of voters out of the system.

Disenfranchisement was especially worst abroad, where only 3% of the already millions of Venezuelans were able to vote. Since 2012, the registry abroad had not been updated and, ever since, there had been little efforts to guarantee the participation of this growing demographic, which significantly opposes the government. In 2018, during the 10-day registration period, the NGO Voto Joven also surveyed 40 consulates and found that 30 of them had suspended the ability to register to vote. The remaining 10 were located in the cities with the highest number of Venezuelans: Madrid, Bogotá, and Santiago de Chile, but had limited operational capacity. This, combined with the legal requirement of regular migratory status to be able to vote, represents a significant hurdle for Venezuelans abroad to participate.

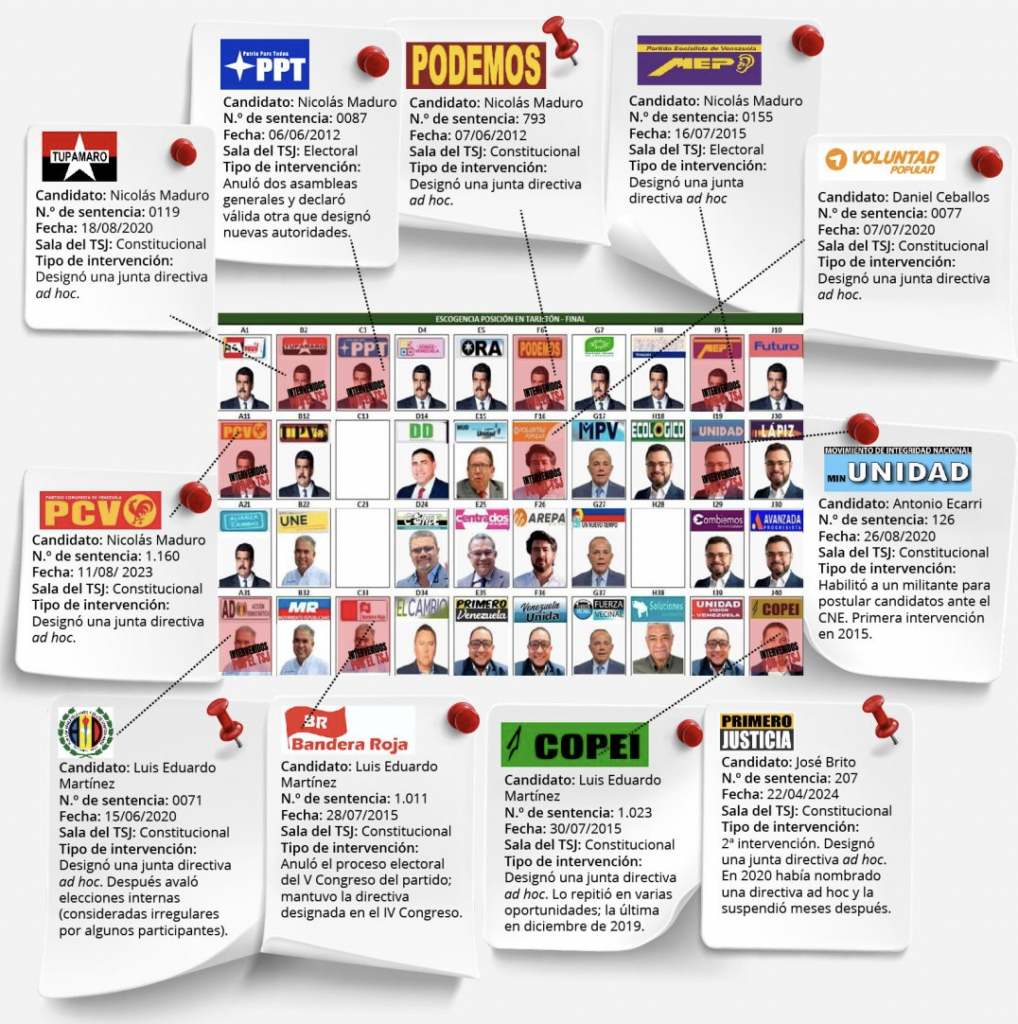

Chavismo continued to be hostile against participation as the 2024 presidential cycle approached. It continued to target political parties. Throughout the 2010s and 2020s, the judiciary took over leftist parties like Bandera Roja, Compromiso País and Patria Para Todos, who had broken ties with Chavismo. This meant that, while their image still appeared in ballots, the organizations behind them would be managed by court appointed officials. It also did the same with traditional opposition parties like Acción Democrática, Voluntad Popular, Avanzada Progresista, Primero Jusiticia (which was just recently intervened again) and COPEI – seemingly to once again confuse voters and limit the opposition’s organizing capabilities. In 2022, the TSJ even did the same with the Communist Party of Venezuela.

The government also continued banning dissidents and trying to limit voter participation. For the 2020 legislative elections, it eliminated indigenous people’s right to vote directly –despite rolling it back a few months later. In the 2021, the TSJ suspended the counting of the gubernatorial elections in Chávez’s home state of Barinas as polls showed that opposition candidate Freddy Superlano was winning. The judiciary called for special elections and barred Superlano and the subsequent opposition candidate Aurora Silva from running. While it ultimately ended up being an opposition victory, the process also included multiple irregularities. Furthermore, in 2022, another referendum attempt was also quickly dismissed by the CNE. It became nearly impossible to compete against the government through electoral avenues.

All of this leads us to the current presidential election cycle, where electoral conditions continue to be severely deteriorated. There have been significant attempts to curtail opposition participation, especially with the efforts to prevent the enrollment of María Corina Machado and her designated candidate Corina Yoris. Moreover, irregularities with voter enrollment both at home and abroad continue. According to Alerta Venezuela, Espacio Público and Voto Joven, about 25% of Venezuelans can’t vote and the promise of improvement that was signed in the Barbados accord appears largely unfulfilled. This doesn’t mean that a competitive election is not possible this year or that we should by any means be hopeless. There is still plenty of time for agreements that would improve the possibility of a fair and transparent outcome. Nevertheless, even if a political transition were to happen, there’s a lot of work to do to reconstruct the sense of trust in the electoral system that is much needed for the country to be a functional democracy.

Featured image: “Pensamiento Único” (2008) by Nelson Garrido.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate