Memes and Posters Against Election Fraud and Gaslighting

When the chavista regime stole the presidential election victory in 2024, I made memes and visuals to control my emotions—without thinking that many of them would go viral

The night of July 27, 2024, in Florida, I went to bed after promising my wife, stressed out but hopeful about my will, that I wouldn’t touch social media or anything that had something to do with Venezuela until the following day. In the morning, once I opened my eyes, I knew I couldn’t hold to that promise. I started right away to message my family on WhatsApp to be sure they were OK and preparing to vote. I sensed them nervous but happy, somehow sure that it would be, at least, the beginning of the end.

While we were preparing breakfast, I kept looking at my phone, anxious with FOMO as every time some major political event takes place in Venezuela. Social media gave Venezuelans abroad a sense of community, because we tend to be quite aware of what’s happening there, and in moments like that it is even more crucial to get some idea of what’s going on in real time. And I talk about getting an idea because, after nine years living in the United States, Venezuela can feel remote and impossible to understand, an alternative reality created by chavismo like in a Black Mirror episode.

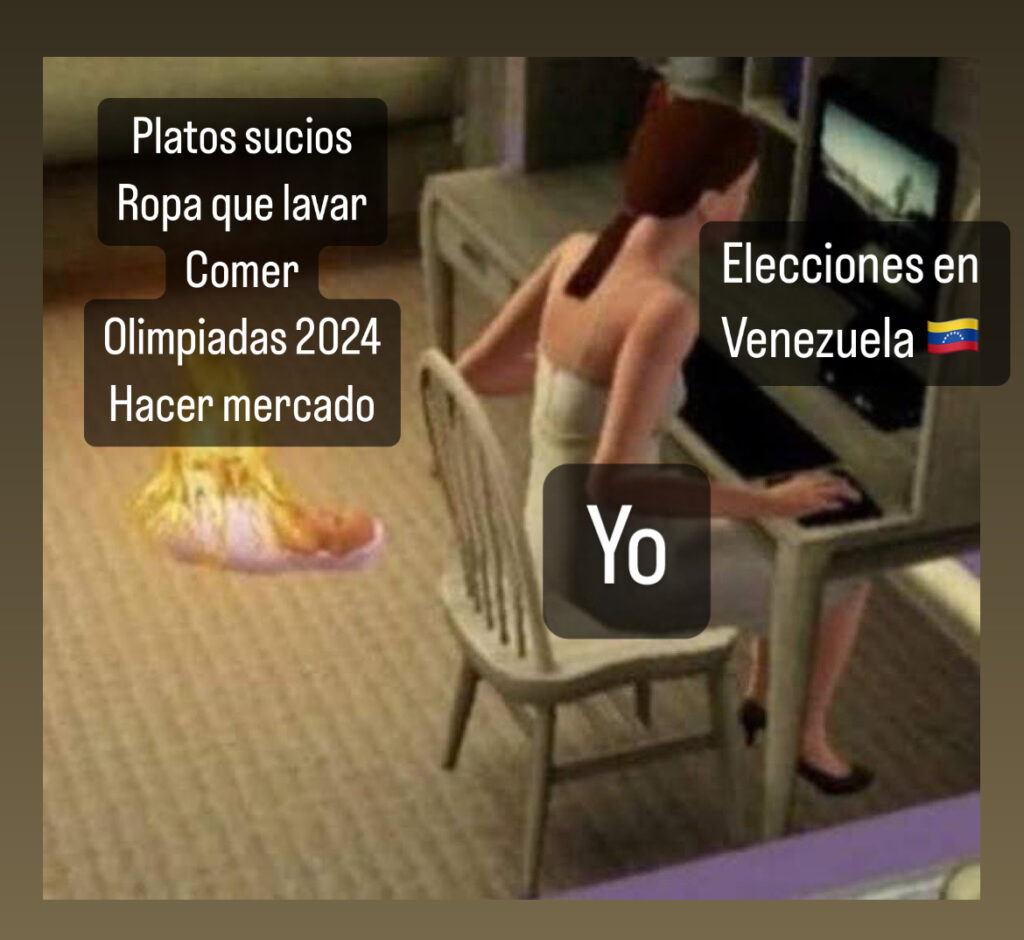

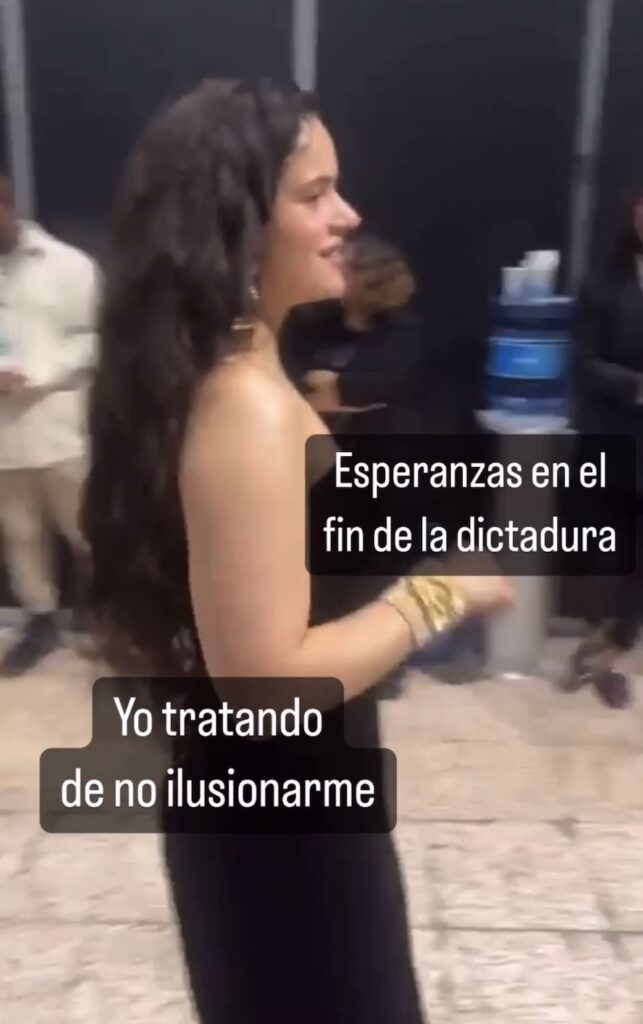

I tried to have a normal Sunday, cooking, doing laundry, but it was impossible to stop scrolling. My mom was sending me pictures of the voting lines, after telling me she had cooked a casserole of soup before leaving the house, following a tradition started by my grandma, who used to cook that same soup before taking to the streets to be the first in the family to vote at every election. In the afternoon, I felt the urge to discharge my anxiety in some “productive” way, by making memes. Amid queer references and memes of past years I found how to connect every tweet or news I read. At the same time, I was following the events by watching the live stream of VPITV on YouTube. I read the live comments, watched what was being reported from the voting centers, and translated everything to memes.

I recognized my friend Ariana González being interviewed. I’m proud of her temperance and clarity when she explains our country’s situation from a gender perspective. I’ve worked with her as a designer, creating content in diverse projects to fight for women’s rights, especially Venezuelan migrants who are frequently abused in the Darién Gap. Of course, we both admire María Corina Machado’s commitment to expel chavismo.

I must confess I know very little about politics besides the news. But I knew something was wrong about Chávez 25 years ago. I remember that, just before the 1998 election, my mom told me that she was worried by the chauvinistic discourse, because we were Colombian immigrants in Venezuela. Years later, when Chávez made it easy for thousands of Colombians to become Venezuelan citizens to secure their votes, we took the opportunity to simplify our lives as foreigners. But even then, no one in my family ever voted for Chávez or any of his candidates in any of the many elections held while the guy was alive.

Back to the afternoon of July 28: hours passed and I kept making memes to release tension.

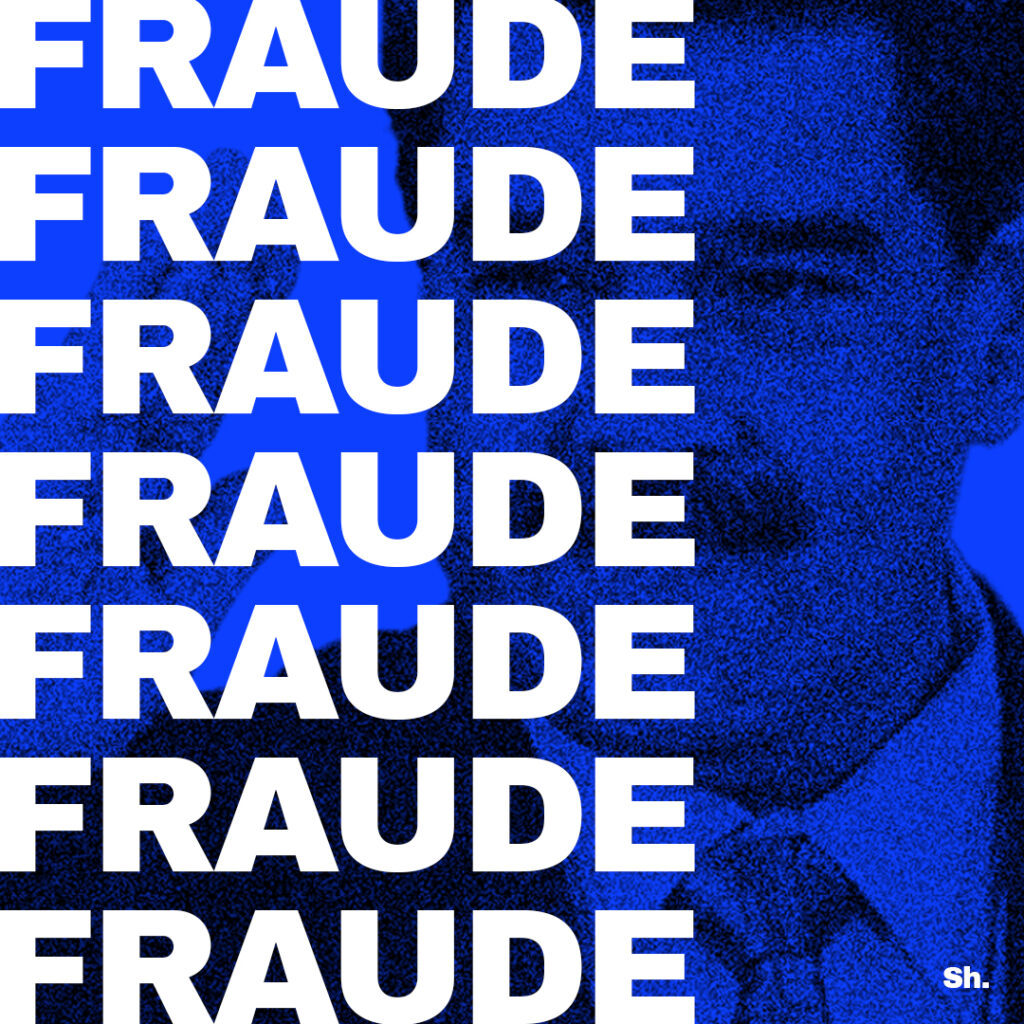

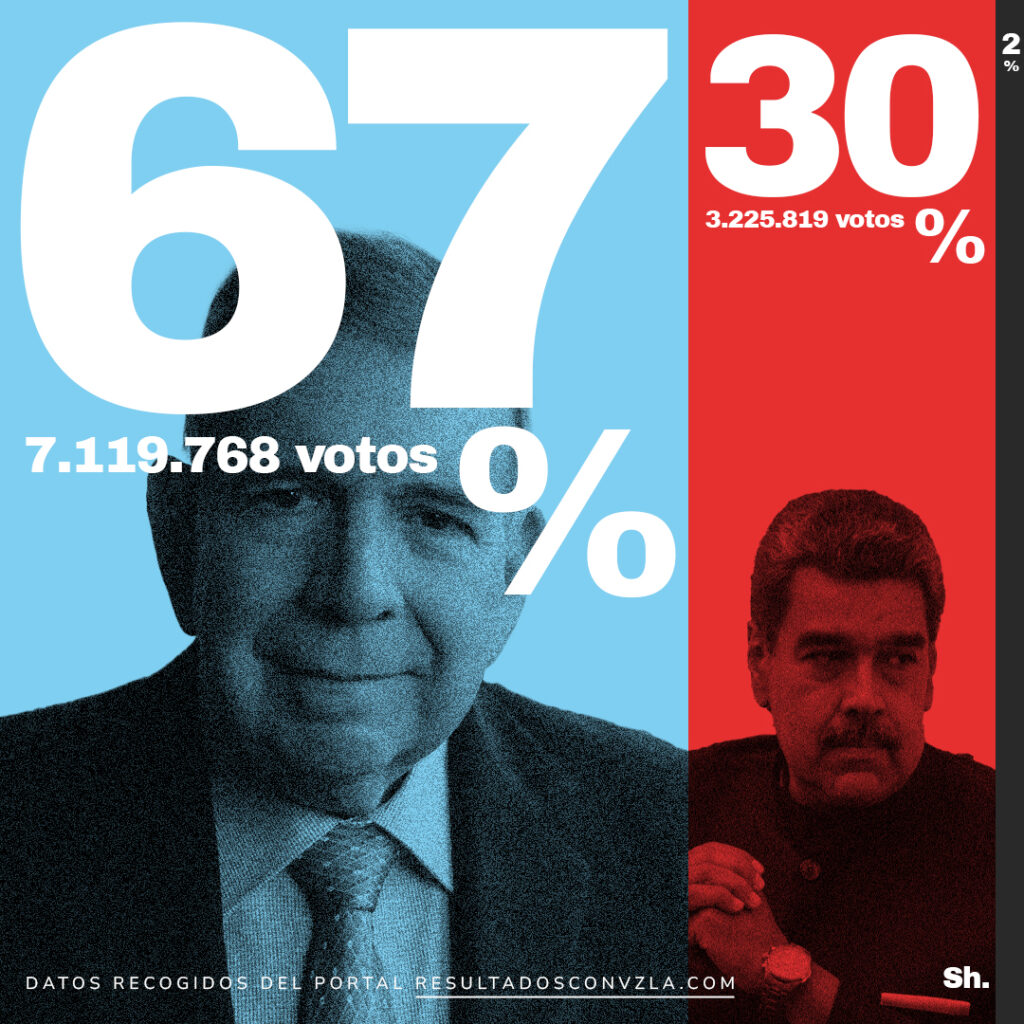

I messaged my dad to invite him to come over and wait for the election results with us. I wanted us to be together when the announcement came, whatever it might be. Our anguish increased every hour. We began to learn about exit polls that pointed at Edmundo González Urrutia as a clear winner. My dad fell asleep watching the TV while my wife stood glued to our phones, defeated by screen addiction. At midnight, when CNE president said that Nicolás Maduro had won, I recorded a video of the moment where one can hear the sullen voices of my dad and my wife letting out their disappointment, and my voice shouting out “MENTIROSO” (lier) to Elvis Amoroso, as if he could hear me.

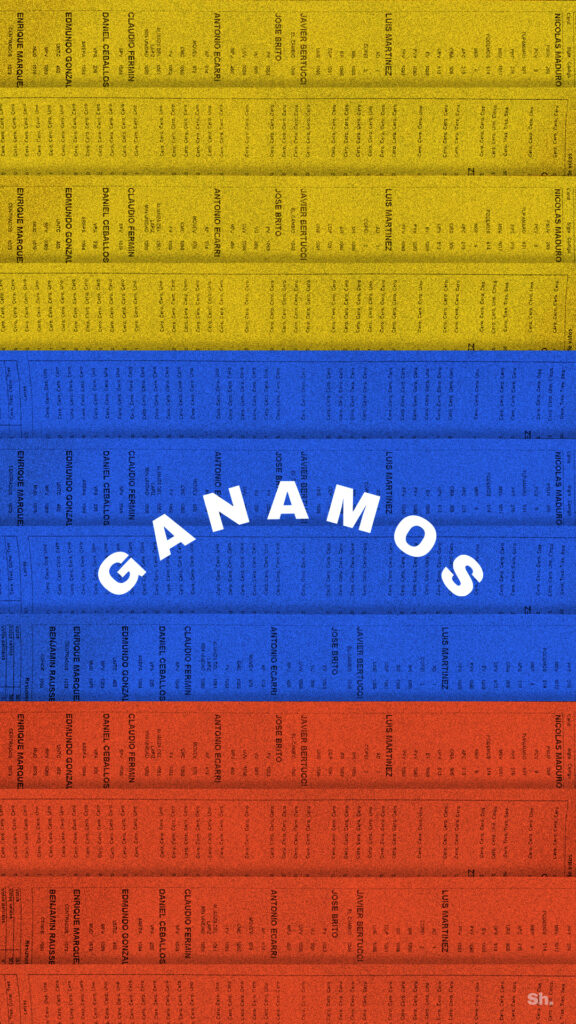

I held my dad, who was sitting on the floor. I cried in anger in his arms and he did what he could to calm me down. Suddenly, as sprang out by some reflex, I sat in front of my computer and started to create an image that expressed my rage. I posted it on Twitter (I refuse to call it X) at 12:12 am of that bitter Monday:

At that very moment, likes and retweets began to rain. Many Venezuelans were, like me, awake and unwilling to accept what Amoroso had just said. Creating that image took me less than ten minutes, contrary to a design process that sometimes needs hours. While the image continued to generate reactions, I was accumulating material to create more, looking for pictures of all the characters of this unending drama.

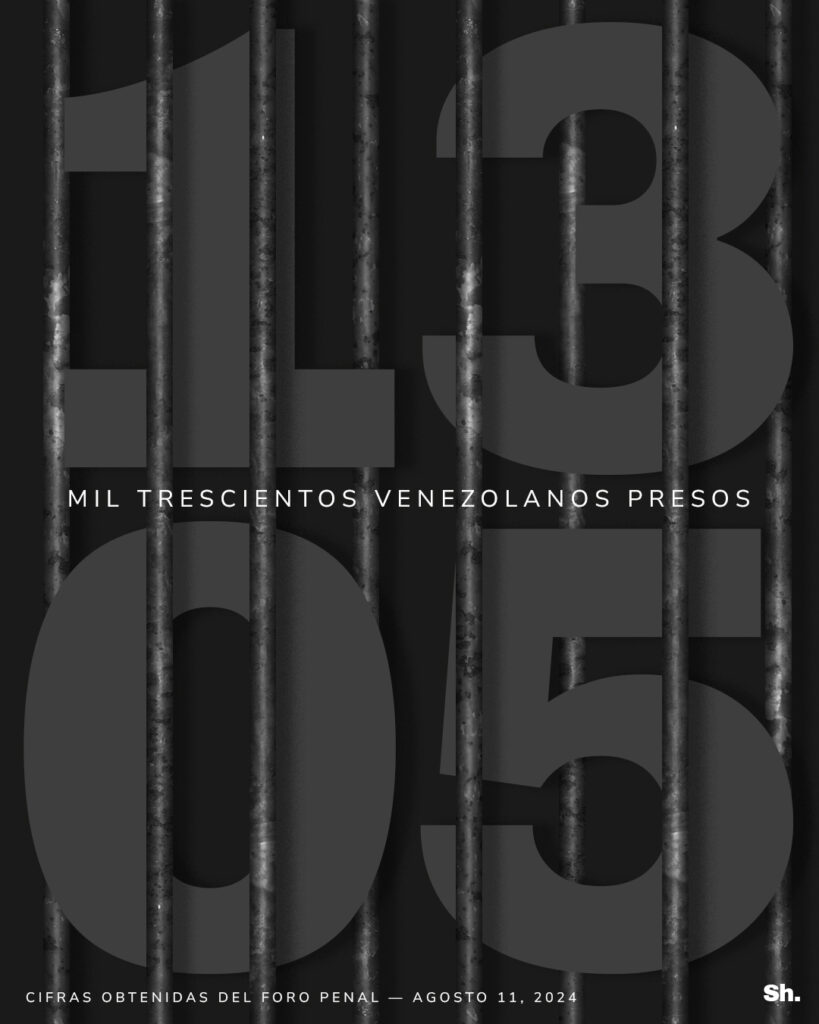

The next day, I couldn’t focus on anything that wasn’t making more of these protest images. I need to vent, take out what was inside me and share it with others; maybe that is only what artists look for. The work day was bitter and burdensome. While people started to demonstrate in several Venezuelan cities, convinced that the government had committed fraud, social media began to spread videos that tried to prove the electoral theft. Polling station witnesses were showing pictures of the voting tallies, the actas, on their hands. We saw a smiling María Corina, assured that she had undeniable proof that chavismo was defeated. Many people was detained that day, and I started to worry about my family. I was doing my job for 20 minutes and going back to make more images and share them on social media, as soon as I finished them. I had to silence notifications on my phone, because every image generated thousands of reactions instantly.

The next day, we learned that security forces in Venezuela were stopping people on the street, checking their phones, and arresting them if they found any evidence that they supported the opposition. I messaged my family there to confirm they were fine, and to ask them to unfollow my social media accounts. I deleted the pictures I had with them on my social media. But my mom texted me: “hija, you keep making your images”.

At that moment, I understood what I was doing. The need to keep doing it became stronger. Millions of Venezuelans in the country were being deprived of the chance to call out the fraud, so people like me were necessary to amplify their voices.

So I decided to change my profile pic and sign every image as “Sh.” to hide my real name. It was funny when someone asked who was doing those “edits”—is that how young people call design nowadays?

On August 4, someone asked me via Twitter DM to create a poster inviting the public to a demonstration in front of La Carlota airbase in Caracas. I didn’t answer. I thought it might not be a good idea to divulge that sort of content when the Maduro regime was kidnapping people just for their opinion. I passed, but I grasped the need of people there to say things without risking their lives.

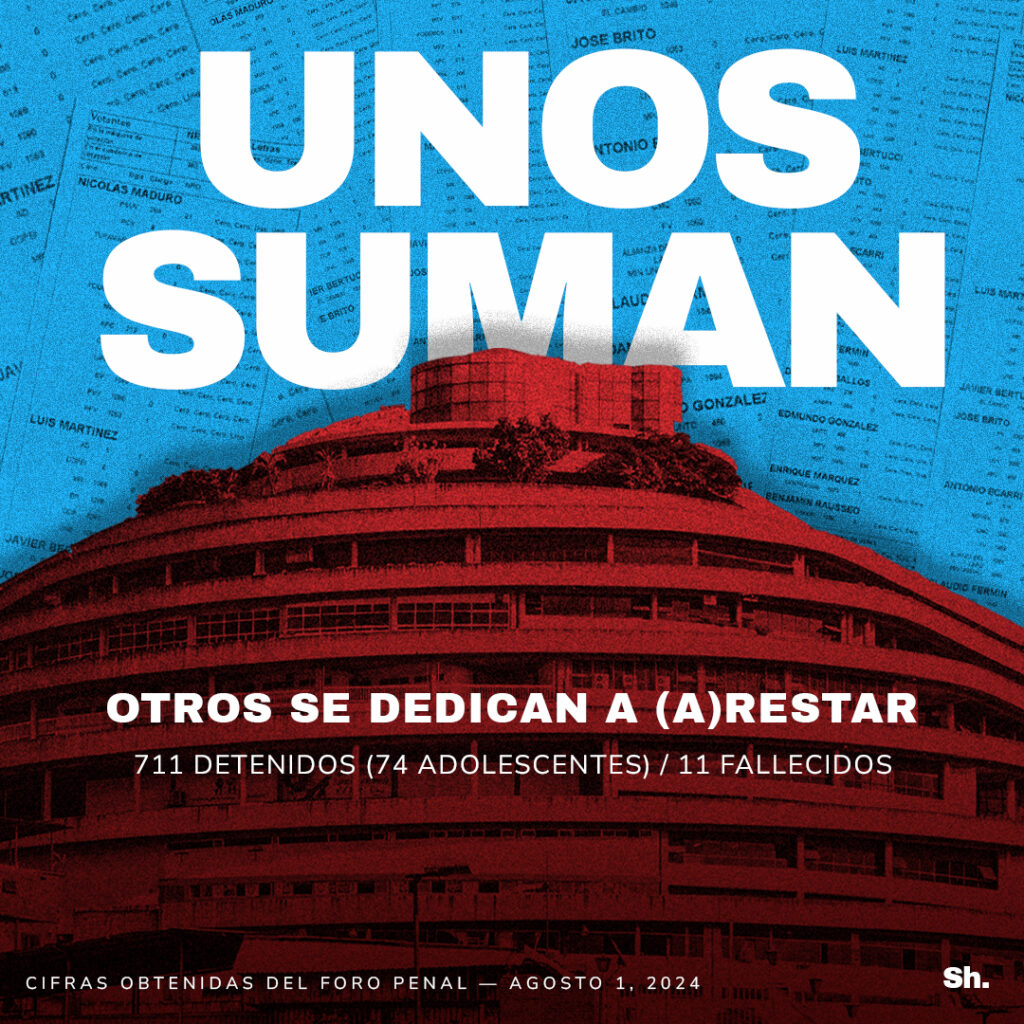

In one of the images I made, I quoted a date from NGO Foro Penal, which was documenting the people detained by the regime. By August 1st, only four days after the fraud, 711 people were imprisoned just for protesting.

One of the most “controversial” images—and therefore with more interactions—was the one asking foreigners to stop “stop explaining Venezuela to Venezuelans”.

Because every time something happens in Venezuelan politics, some guy who doesn’t know the country comes to explain or justify what chavismo has done, as if he had lived under chavista rule and knew how it is to feel persecuted, even if you live abroad. That image clicked with thousands of people, even among those who oppose—and on this they are often right—exiled Venezuelans who try to influence voters in the countries where they now reside.

With the repression that followed, more designers and artists started to create images, just like me. Edo and Pinilla, among others, joined the graphic protest. On August 9, Maduro blocked Twitter and people in Venezuela turned on their VPN to stay connected and informed. Art can produce metaphors that help to understand and talk about difficult matters.

I don’t know how one of the images I made ended up on a truck with LED screens going about the streets of New York, inviting people to protest against Maduro.

What was amazing amid the horror of those days was to see Venezuelans abroad raising their voices to fight against the dictatorship. It was beautiful to attend demonstrations and see that people wanted to be photographed with my pieces. It was nice to see that we were agreeing on anything.

I don’t know how I managed to be productive at work. In those images, I addressed the election results, the political prisoners, the CLAP bags, the support that chavismo still shows on social media, and how evil the regime is.

In the following months, the drive to protest against the fraud—which was properly proved by every possible expert and organization—dissipated because, I guess, the discourse fades out even when it says important things. One must leave behind what one can’t change. Those days and weeks consumed most of my energy and the same must have happened with millions of Venezuelans abroad, artists included.

It was a very productive stage of my career design… not lucrative at all, though. However, I am happy to contribute to the collective message and to the fight against the gaslighting of those who try to hide the dictatorship.

We are eight million Venezuelans abroad, and among us are artists who want to divulge our cry for freedom. I know that, whenever we are, we are ready to hit the bad guys with everything we got.

And please don’t forget, even if it’s painful, that…

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate