Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles’ Quest for an Alternative National Epic

One of the most celebrated writers of contemporary Venezuela just published the first of four novels around a fictional music band. Its goal: To use that story as an indirect mirror of our country’s mutation

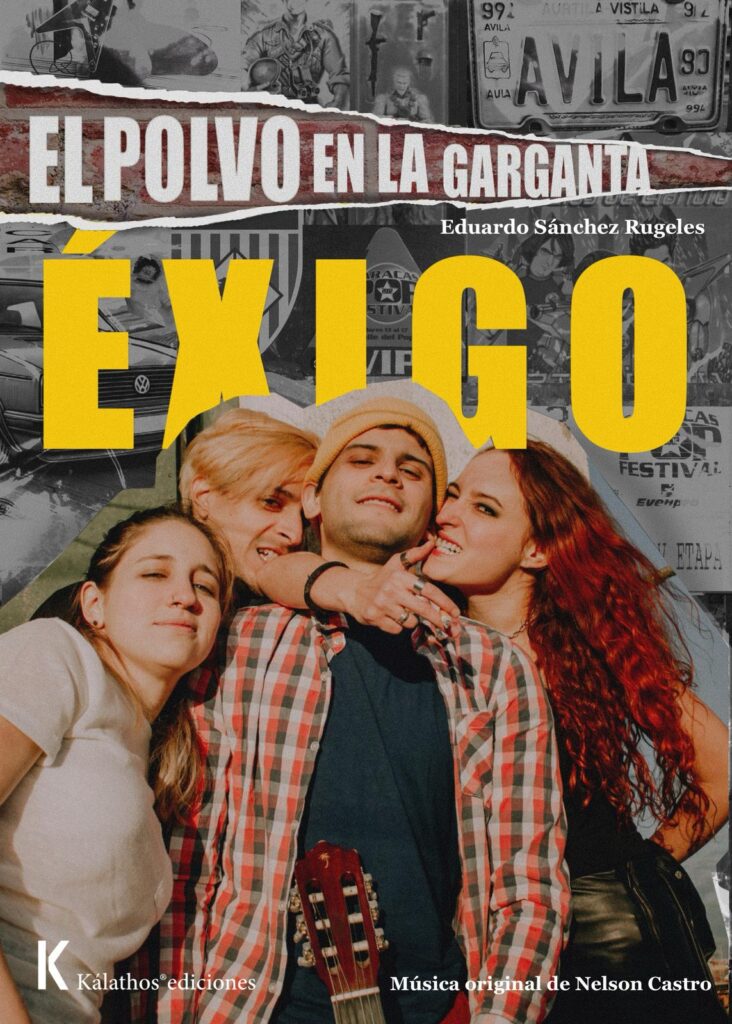

First, we saw the four musicians on social media, playing clips of their songs, looking like a 1990s rock latino band, before understanding what they really were. The intriguing name of the project was Éxigo. It had its own Instagram account and we all could meet their members: Daniella, Shena, Frank and Willie. Then we saw that the Venezuelan writer Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles had something to do with it. And at some moment, we realized that the band does not exist. They are the main cast of Sánchez Rugeles new novel: Éxigo, el polvo en la garganta, which just came out in Spain.

The novel is the first installment of a series of four: El polvo en la garganta, Camino a la perdición, Esclavos del juego and La soledad esculpida en piedra. They come with an album of original music and the mission that will keep Sánchez Rugeles quite busy for the next years: penning a thousand-pages narrative cycle that tells, from the alternative point of view of the band’s rise-and-fall arc, how Venezuela experienced a quarter century of chavista rule. So Generation X. So Sánchez Rugeles.

A novel to tell a nation

This transmedia literary project was born out of a movie, Almost Famous (Cameron Crowe, 2000). “When I watched it,” Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles remembers in a Madrid café, “I started to slowly brewing the dream of writing a novel about a fictional band. That was ten years before publishing Blue Label/Etiqueta Azul (his breakout novel, from 2010). During that time, I had to grow in this trade, writing other things without coming back to that old idea to give it a more serious thought.”

Two external events would rescue the Éxigo project from the drawers of the writer’s table. In 2016 the Swedish Academy awarded a musician, Bob Dylan, with the Nobel Prize in Literature, and in 2017, during a visit to Caracas, Mario Vargas Llosa said that Venezuela was ready to have its own epic. People started to debate about the words of the Peruvian master, while Sánchez Rugeles found himself dusting off his dream of a fictional band, formed by two guys and two girls, and wondering if that model could be the backbone of a more ambitious endeavor: to produce that national epic suggested by Vargas Llosa.

Some people said that Vargas Llosa’s invitation to produce a great national novel was anachronistic; Sánchez Rugeles was, instead, ruminating that if he found a way to tell the story of Venezuela under chavismo from a tangential point of view, not looking directly at the fire but registering the ash falling on our entire world, he could achieve a narrative cycle that encompasses the country’s transformation without focusing on Hugo Chávez. “Building the great contemporary Venezuelan novel is a tempting challenge, maybe doomed to fail but alluring anyway. Maybe literature could find some hints to understand the unravelling of our citizen life, the wreck of the nation, the loss of our institutions. Chavismo is a defeat like that one foreseen by Rafael Cadenas in his famous poem, which deserves to be told in the form of a novel”.

“I am a music lover, not a musician. I couldn’t write songs. So I turned to my friend Nelson Castro, who could.” This has a precedent: for the novel Liubliana, Venezuelan composer Álvaro Paiva Pinto wrote a score after the book was published.

“I’m not against the idea of a sort of Las lanzas coloradas 2.0 that offers an account of the catastrophe of our times. I imagine it as a story of despair told by many characters, maybe across several parts. I would admire the writer who would embark on that endeavor.” The writer points at those novels written at the sunset of the Gómez regime, since the 1930s, that drafted an unprecedented understanding of the nation: Arturo Uslar Pietri’s Las lanzas coloradas (1931); Rómulo Gallegos’s Doña Bárbara (1929) and Canaima (1935); Enrique Bernardo Núñez’s Cubagua (1931); and Miguel Otero Silva’s Casas muertas (1955). Novelas totales written with the goal of describing a paralyzed, defeated country. While Silva’s La muerte de Honorio (1963) and Se llamaba SN by José Vicente Abreu (1964) reacted against the violence of the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship, before País portátil (Adriano González León, 1969) or Los topos (Eduardo Liendo, 1975) are idealist novels that dared to denounce the dark side of the newborn democracy. The 1990s crisis and the surge of chavismo restarted the Venezuelan literature’s focus on history, with Ana Teresa Torres’ Doña Inés contra el olvido (1992), Federico Vegas’ Falke (2004) or Francisco Suniaga’s El pasajero de Truman (2008), among others. A collective tale that many authors have been building for a century, and continues in our times.

Songs for a lost world

Once Sánchez Rugeles finished the novel he was writing at the time, El síndrome de Lisboa (available in English and in the works for a film adaptation, as happened with Jezabel), he started to work on Éxigo. The Alexandria Quartet, Lawrence Durrell’s four-novel masterpiece about mid-century Alexandria, emerged as a literary model for what started with a cinematic infatuation. A third big frame for the project is the corpus of musicians’ biographies, which Sánchez Rugeles devoured. Then he realized this would be a transmedia enterprise.

“I saw that all those biographies had pictures and even links to songs online or videos in YouTube. I went crazy about doing the same and organizing that reading experience to a different level.” It was about creating a trace of pictures, videoclips and songs of a band that never existed. “I am a music lover, not a musician. I couldn’t write songs. So I turned to my friend Nelson Castro, who could.” This has a precedent: for the novel Liubliana, Venezuelan composer Álvaro Paiva Pinto wrote a score after the book was published. Castro, who lives in Paris, jumped on the Éxigo train from the start. He and Sánchez Rugeles spent a year creating the songs, interchanging music and lyrics on WhatsApp. “I gave Nelson the context for every lyric, which are supposed to be written for the two singers and composers of the band, Daniela and Sheina. I told him in which moment of their lives they would write them. That way, we finished the entire album.”

In 2019, Sánchez Rugeles began to look for the cast. He knew these four young Venezuelan musicians in Madrid and told them the entire argument. They accepted immediately to be part of the experiment. This is how Amaia Kintana became Daniella, Andrés Adolfo Ruiz became Frank, Willie invaded the body of Luis Fernando Campos and Shena did the same with Graziella Mazzone. Estefania Pomares made more than 300 pictures of them and they started to play the songs. “At that moment, I hadn’t written a line of the novel, but I already had my four main characters in front of me, alive.”

The time to finally sit and write Éxigo: el polvo en la garganta was dictated by the arrival of the pandemic. The first draft was ready after four months of early-morning sprints, knowing from the start it would be the first of four novels. An agent who did nothing but insisted several times in taking things out of the initial versions caused a delay, until Sánchez Rugeles rescinded the contract. Finally, he found a home for the project, Kalathos, a binational Spain-Venezuela publishing house from the owners of the namesake bookstore in Caracas. Now, the book is at bookstores in Spain and Venezuela, and available on Amazon in North America. Éxigo: El polvo en la garganta came out with the entire cycle already drafted. Sánchez Rugeles is in the middle of the second novel.

The transmedia side of the project is not the only thing that makes it unique. Music is not a frequent subject in our literature. There aren’t many stories or novels with musicians at the front, save for a few exceptions like Liendo’s Si yo fuera Pedro Infante. It’s like baseball: we love it, but it isn’t a common trope in our fiction. Our musicians have been, on their part, more focused on love, dance and nostalgia, than on registering current affairs. For Sánchez Rugeles, “maybe music has been there always, in the background, as a witness to history, but perhaps our cultural industry has preferred to give more visibility to romantic, escapist lyrics. However, we can find Venezuela and Caracas described in many songs by the big band Billo’s, and criticism about the loss of traditions in the music from the Llanos. In Zulia, the gaita always had a discourse fighting power. Protest singers like Alí Primera wrote pieces like ‘Canción mansa para un pueblo bravo’. Little known songs by Franco de Vita and Yordano are gorgeous chronicles of Caracas, ‘Plaza del centro’ and ‘Finales de siglo. And we have Desorden Público as well. I feel the music did register our history, but the industry is uncomfortable with that tone. Especially now.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate