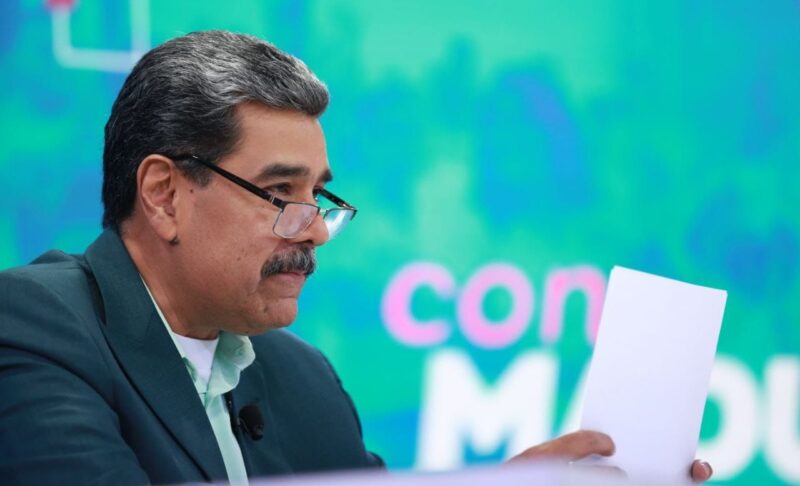

Maduro & Co. Push Their Agenda on the Mega-Fraud’s Anniversary

Maduro struck quite a deal with Donald Trump: he released a few political prisoners, left key dissidents behind bars, and got Chevron back on Venezuelan soil #NowWhatVenezuela

#NowWhatVenezuela keeps you informed about what’s happening deep inside la patria—from headline-making events to underreported stories that provide the clearest picture of our reality. This digest is published weekly.

Join our official channel through this link.

Human trades, oil concessions, and a conveniently “reelected” counterpart

A prisoner swap with the U.S. and El Salvador, a leak about Chevron resuming operations, a municipal vote, and the anniversary of July 28th unfolded in less than two weeks. These days brought joy and relief for dozens of families that finally got to embrace loved ones who had spent months held in torture centers or kidnapped in third countries. For Maduro and his inner circle, this has been a month of both symbolic and concrete gains. They were holed up in bunkers and government offices in Caracas exactly a year ago, calling on the remaining colectivos and a handful of security agents to shoot at ordinary Venezuelans who had taken to the streets to protest the mega-fraud. Today, Maduro celebrates while his historic rival abroad contradicts itself, speaking of drug trafficking and accusing him of heading a cartel—while simultaneously granting him access to a huge source of clean money.

It may not be permanent (although as of yesterday it seemed like an official decision), but the “maximum pressure with teeth” that figures like Marco Rubio and Mauricio Claver-Carone promoted barely lasted three months. (Claver-Carone said they would go all out against Maduro in April before exiting the administration in May.)

Jorge Rodríguez is having his most useful moment for Miraflores since July 28th, 2024, as the communication channels between Washington, D.C. and Caracas are now active and on full display. José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero is back on the scene, and efforts are underway to “empower” the clientelist non-chavistas. The prisoner deal between El Salvador and Venezuela resulted in the release of 10% of Venezuela’s political prisoner population, according to figures from Foro Penal. But 853 still remain behind bars. The revolving door keeps spinning, and María Corina spoke of 20 new detentions following the tripartite agreement.

Why it matters: None of the “high-profile” prisoners tied to the 2024 campaign were included in the final list, such as Machado attorney Perkins Rocha and politician Biagio Pilieri (both of whom are close to the opposition leader and among the 16 political prisoners held in isolation at El Helicoide).

Nor were civil society figures like Provea’s Eduardo Torres, or more “moderate” politicians like former presidential candidate Enrique Márquez. Those who were released include former minister and dissident chavista Rodrigo Cabezas, data analyst Gerardo Cacique, and economist Daniel Cadenas (the latter two known for their work on inflation in Venezuela), who went missing in June.

As our Political Risk Report warned two weeks ago, Zapatero was involved in drafting the release list while working closely with Jorge Rodríguez (Maduro even congratulated the Spanish former president during a televised call), and with Henrique Capriles and Stalin González acting as intermediaries between the state and relatives of political prisoners. Both politicians were “elected” to the National Assembly in the May parliamentary vote while endorsing negotiations for this sort of action.

Of course, such a role is more about performance than substance. Stalin González recently said that “only those in power decide who gets released,” and in fact, neither he nor Capriles have any real negotiating power. The part they’re playing depends entirely on the government’s will and on political convenience—like what just happened.

Their local counterparts also earned points with chavismo after Sunday’s municipal vote. Jorge Rodríguez had claimed PSUV would finally seize control of wealthy municipalities like Chacao, Baruta, El Hatillo, and Lechería—but that didn’t happen. If anything, the claim now seems like a case of reverse psychology. This week, after chavismo claimed 285 mayoralties and Fuerza Vecinal retained a handful of blue strongholds, Rodríguez congratulated faux opposition parties, Fuerza Vecinal, and the governor of Cojedes as the new “representatives of the Venezuelan opposition.” Vamos Vamos Cojedes, the party of non-chavista leader Alberto Galíndez, has become a favorite of the regime in the Llanos. According to official announcements, it has won every election in the state since July 28th, including nine mayoralties this Sunday. As expected, no vote tallies or proof of those victories have been presented—for Galíndez, for Fuerza Vecinal or for anyone.

Anniversary #1: In her commemorative speech, Machado described July 28th as an “irreversible turning point in our history” and called Maduro “defeated.” She also urged the military to stay alert and prepare for a “decisive moment,” and called on “all structures within Venezuela” to organize clandestinely in preparation for “civic action when the time comes.” Figures aligned with Capriles and Un Nuevo Tiempo—who have not exactly been targeted by persecution—were the first to criticize Machado’s message on X, as if it were news that thousands of people have been hiding since July 28th.

Relevant reads: The Venezuela en Movimiento human rights alliance just released a report titled The Grey Book of Nicolás Maduro, which documents the erosion of freedoms in the six months since July 28th. It also highlights the semi-clandestine status of many civil society organizations, now forced to lay low and stay silent to avoid repression.

A “binational” SEZ on the border?

According to the Petro government, the new memorandum for a shared Special Economic Zone will cover Norte de Santander and La Guajira (“with the possibility of including other border departments”), as well as Táchira and Zulia.

These just so happen to be the areas with the highest concentration of ELN activity on both sides of the border.

Caracas says the deal will include investments in “energy, electricity, tourism, and transportation,” as El Tiempo noted. The rest of us are left guessing what that even means—though Maduro claims China, India, and Turkey are all interested in pouring money into a conflict zone controlled by guerrillas and drug traffickers.

Why it matters: To most observers, this looks far less like economic development and far more like a free-roaming agreement for armed groups and illicit activity. Petro first publicly floated the idea in early March, about six weeks after the Catatumbo crisis (also remember that Maduro is holding 28 Colombian nationals in Venezuelan prisons). We’ll also have to see how this SEZ fits into the Colombian government’s plan to invest $600 million in the so-called Catatumbo Pact, which, according to the United Nations, aims to strengthen the state’s presence, improve infrastructure, and bolster local economies in the region.

More information: Just before being convicted in his country for a case linked to his years in government and collusion with paramilitaries, former president Álvaro Uribe said the binational SEZ is a step toward handing Colombia over to “international criminal networks and their protectors like Maduro”—which doesn’t sound far-fetched at all. The SEZ debate has taken a back seat in Venezuela in recent days, especially after María Corina voiced support for Uribe in a display of automatic solidarity that mirrors how chavismo has embraced fellow authoritarians across Latin America.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate