Inside Ciudad Guayana’s Illegal Gold Retail

The gold rush in the south-east quarter of the country is helping all kinds of people deal with economic hardship. But gold in grams is replacing the legal currency and the criminal industry has found another realm to control and get profits

The mantra can be heard everywhere in the main hall of the shopping center: “Gold, gold, gold, gold, and dollars!” These are the pullers, people who sell gold and dollars —or more accurately, intermediaries who connect prowling sellers to a specific buyer.

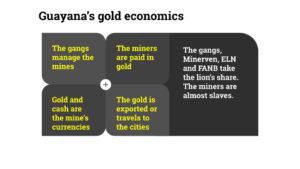

Gold retail in Guayana is another consequence of the hyperinflation that has shattered purchasing power and production, created unemployment, and incentivized a thriving illegal mining culture in the southern Bolivar state. Gold extraction is greatly attractive for hundreds of people and creates profits between the deposits and the larger cities, tied to corruption, ecocide, massacres, extortion, armed gangs, and the ELN guerrilla.

Gold as currency

Gold retail and its use as a currency are a frequent practice all over the state. The little development of electronic banking in the south and the hyperinflation that makes any amount of banknotes useless to buy basic goods, have led the market to using other exchange values, such as the dollar, Brazil’s real (highly prized at the border) and gold, the latter due to the gold mining rush.

The strength of this business declines in the state’s two largest cities, Ciudad Bolivar and Ciudad Guayana, but remains a prime economic mover in the area. The Ciudad Alta Vista I mall, a withered icon of a Ciudad Guayana full of money and productivity in the 90s, embodies this bubble amidst barbarity with its lonely halls, closed stores and blinking lights, and has become a gold retail reference, attracting scores of buyers.

“I don’t feel good with this. I know they’re destroying nature, and there’s great evil down there (in the south.) Too much death, too much ugly stuff… it’s tough.”

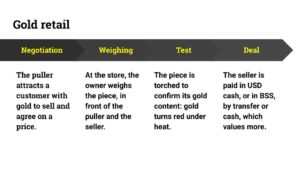

Several of its stores, now closed because of the economic debacle, still keep the front and the space of better times. They’re now a sort of micro-Persian bazaar of gold: dozens of people tour across dozens of cubicles with buyers. Amid the sound of bill counting machines, piles of cash larger than desks, burners to test “mine gold” and, of course, lots of gold grams, or rather “gramas,” as people in Guayana call the gold gram, apparently coming from the Portuguese of Brazilian illegal miners, called garimpeiros. A “grama” is ten “points” of gold, and one point equals one tenth of a gram.

“The greatest of all”

The “mine gold” is gold ore coming from the southern mines, either brought by small miners who receive it as payment, or by the surrounding commercial activity.

People can buy gold in one of two ways: with their own capital or as “closers.” The first consists of buying mine gold, turning it in small ingots, analyze them to certify their purity and store, or sell, that “pure gold” as needed.

The second method uses capital supplied by a “wholesaler” who demands a specific amount of pure gold in return. The business is buying (or “collecting,” as locals say) mine gold at a lower price, smelting it and analyzing it to give it to the provider of capital. The difference between the original amount and the costs of collecting, smelting and certifying the gold is the profit.

The identity of these wholesalers is a mistery. Everyone agrees that they’re working for “someone,” and “it could be government people, the military, big shots criminals… we don’t know. Because the wholesalers we work for, in turn work for someone up top, and so it goes until it reaches the top boss, whom nobody knows.” People in the cubicles repeat this as if it were a script.

They all know the practice is illegal. They know that the law establishes the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV) as the only institution to buy gold coming from “any mining activity” in the country, although in 2015, the same year when this law was enacted, the government allowed “gold providers” to sell to the BCV pending registration.

The business is buying (or “collecting”, as locals say) mine gold at a lower price, smelting it and analyzing it to give it to the provider of capital. The difference between the original amount and the costs of collecting, smelting and certifying the gold is the profit.

“Here, most are illegal. Some say they’re registered in the BCV, but nobody knows,” says a puller in the main hall. Meanwhile, gold replaces the bolivar. In Guayana, it’s common for people to purchase real estate or expensive assets, such as vehicles or high volumes of merchandise, with dollars or gold. The transactions usually involve “analyzed gold,” whose carats have already been determined, along with its exchange value. That’s why “analyzed gold” is more valuable than “mine gold.”

The tip of a very dark iceberg

For José Prat, National Assembly lawmaker for Bolivar State, it’s key to understand that gold retail and other gold transactions are a minor piece of the mining industry that involves corruption, massacres, extortion, environmental crimes and embezzlement of the nation’s assets. “Since all of that comes from an illegal practice, which is the mining exploitation in those conditions, all derived activities are also illegal.” Prat voted against the presidential decree officializing the creation of the Orinoco Mining Arc.

According to Prat, this market is only a small part of the huge bounty amassed by criminal gangs, military guerrillas and corrupt officials in the south. “The remains of that is what circulates here. We don’t know where it ends. Most of it is taken abroad through hidden roads.”

But despite legal implications, the business is booming. You can ask “Alejandra”, a “closer” who supports her two daughters and her parents with her work; or Luis Vallenilla, a 24-year old puller who found in gold a way to survive the crisis. “Last year, I was working in Venalum as a welder and earned Bs. 2,000 per week. That was nothing. Then I joined a small company and earned Bs. 60,000 per week, but that wasn’t enough either. I make than in one day now.”

The business is also prosperous for 27-year old Enrique Bello, who just got Bs. 91,000 in cash for 0.91 gold grams. He had a career in Administration which he abandoned due to economic hardship, and now he retails gold to bring food to six relatives.

But happiness is never complete, at least for David Lucas, a 26-year old puller who, despite his economic stability in the crisis, still feels remorse for the background of that activity. “I don’t feel good with this. I know they’re destroying nature, and there’s great evil down there (in the south.) Too much death, too much ugly stuff… it’s tough,” he says, even though he sustains his couple and his three children with this job.

Vallenilla shares the feeling and sums up the idea with an old miner’s tale: “gold is cursed. You take it from nature and God punishes you for it. That’s why you have to sell it as soon as you extract it. If you keep it, bad things will come.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate