What's Left of the Venezuelan Opposition

The year is half gone and Maduro’s grip on a devastated land looks secure. The hype surrounding Juan Guaidó is but a dim and distant memory. Is opposition politics even possible in Venezuela in 2020?

Photo: Centro de Comunicación Nacional

Has the Venezuelan opposition tried everything? It sure looks like it. Let’s review the scorecard: general strikes, election boycotts, election participation, pressure in the streets, marches, negotiation, mediation, more elections, winning elections (!), skipping illegal elections, international negotiations, more street protests, disavowing an illegitimate president, swearing in another president, taking over Venezuelan assets abroad, looking for hired guns, and many more ranging from the cautious to batshit crazy ideas.

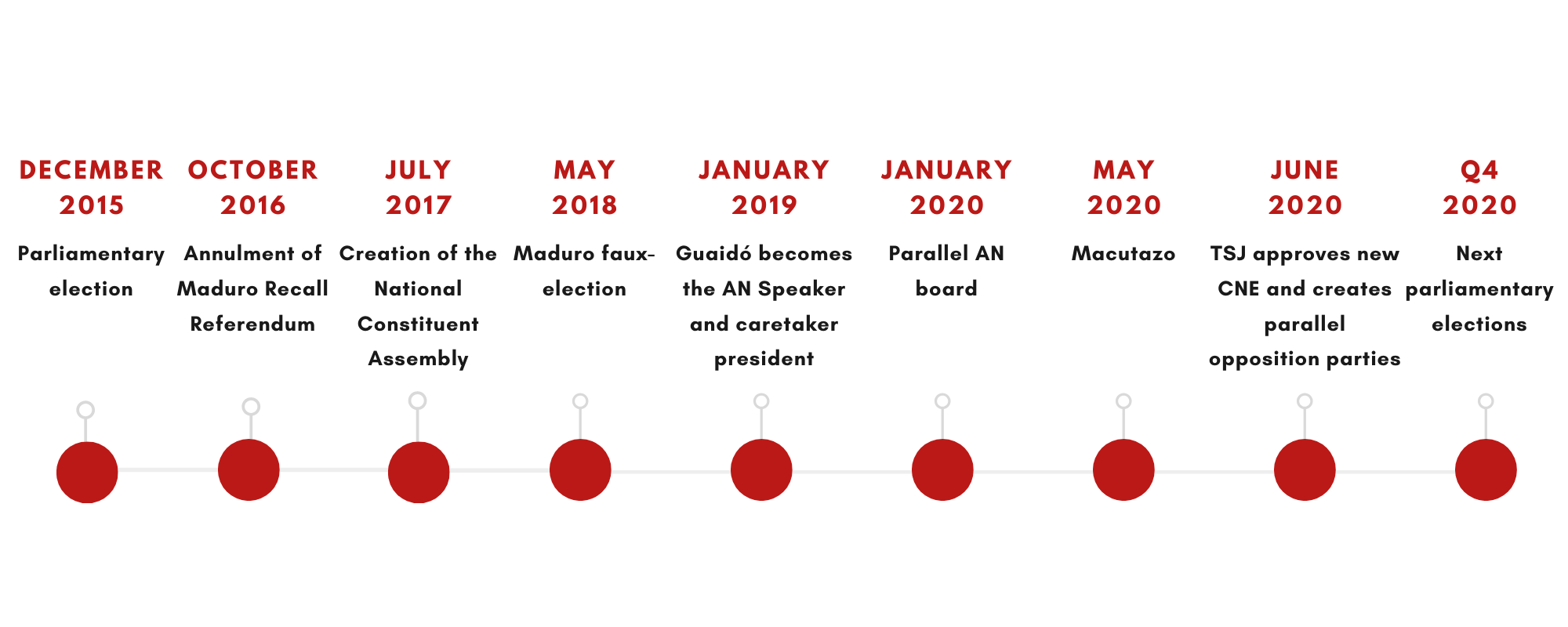

Almost all the opposition political actors have had their shot. Primero Justicia (PJ) led the 2015 legislative elections, Acción Democrática (AD) pulled the rug from under PJ and headed the opposition-held National Assembly during its first year, Henri Falcón’s faux-opposition stepped in during 2018 to oblige Maduro in his illegal re-election, and, finally, in 2019 the more audacious had its turn at the bat with Leopoldo López at the helm and a more aggressive approach which included a couple of failed attempts to set off an uprising against the regime.

It’s been exhausting. By the end of 2019, it was clear that chavismo, once again, had bested the opposition during what, up to that point, had been its most precarious year. Maduro had created a sort of illusion of economic coherence and had been rendering caretaker president Juan Guaidó somewhere between powerless and ridiculous, a mere decorative fixture in our political life, at least locally. When 2020 came around, we saw a couple of attempts and interesting moments by the opposition to recapture the initiative in the international arena. But then came COVID-19, Operation Gedeón, and the chavista assault on opposition parties.

Venezuela’s legitimate legislature, the National Assembly, is supposedly the center of any democratic representation (and hope). But at this moment, what’s the National Assembly doing?

Any discussion about our National Assembly must start by saying that the lawmakers and their teams have been submitted to a brutal campaign of intimidation and harassment. Many have been thrown to jail or forced into exile. Juan Guaidó, the Speaker, is currently holed up in an undisclosed location. The remaining deputies were gathering in different places and now they must turn to sporadic debates through video conferences, in part for social distancing reasons, but also to avoid police harassment. Even the Legislative Building is under siege: members of the National Assembly have no access to the Legislative Palace (which is now used only by the regime-sponsored AN leadership, led by Luis Parra and a bunch of deputies the regime plainly paid off to switch sides). With its powers erased via ANC and TSJ, and no wages until the recent aid package from abroad (which ignited internal disputes for the distribution of those funds between the parties) is approved, the members we elected in December 2015 face daunting obstacles at every turn. This extreme set of conditions keeps worsening with the TSJ recently handing control of opposition political parties to the deputies the regime controls.

In this context, the last legitimately elected institution we have, the only vestige of Venezuelan democracy, is reduced to voting on laws nobody enforces and putting out statements that few people read. A body that cannot function as a real parliament and locked in a neverending set of petty squabbles among its members.

They have tried every card on the deck, and pretty much every opposition player has been on the spotlight. Today, can there even be opposition politics in Venezuela?

Photo: The Caracas Chronicles Team

Is Juan Guaidó still the “leader of the opposition”?

With net approval numbers in negative territory (like all leaders, on both sides), Guaidó has been taking the bulk of the blame for his failure to deliver and looks increasingly isolated, besieged by competitors inside the opposition and living underground. Of course, his failure arguably has more to do with problems managing initially sky-high expectations due to a lackluster communication strategy.

While the regime recognized the AN Speakership as belonging to the head of the parallel AN leadership, Luis Parra, Guaidó retains international support, especially in the U.S. But even that is now stained by Donald Trump and John Bolton’s memoir. His visibility abroad has diminished, with the Venezuelan case being displaced by so many other crises around the world. At home, the caretaker president is focused on occasional tweeting, staying out of jail, and keeping his speakership through fraught negotiations with the four main opposition parties.

His mandate was prolonged by the legal AN in January 2020 due to his international recognition, so Guaidó continues to style himself presidente encargado. That means little to most Venezuelans; but yes, he holds the highest democratically elected political post within the opposition.

What happened to the regime’s effort to create a parallel rubber-stamp National Assembly?

Using the financial muscle of top crony Alex Saab to bribe deputies, the regime managed to break the opposition majority and installed an alternative board, with Luis Parra as the Speaker. Parra’s leadership is not recognized by the countries that accept Guaidó’s claim to the caretaker presidency and has not been enough to get AN-approved credits and contracts with Russian oil companies, for instance, but it was enough to at least close down the rest of the deputies’ access to the Legislative Palace. It was the cue for the recent expropriation of the opposition parties, and started the route to rigged parliamentary elections scheduled for December 6th, that would likely end with a parliament completely controlled by the regime (besides the illegitimate ANC; of course), composed of deputies who come from opposition parties but accepted to play under the dictatorship’s rules. This is the regime’s best bet to control something similar to a parliament that can be recognized by some of its international allies, although it’s entirely possible that it won’t work.

Where is the real opposition then?

Right now, besides the small July 16th Fraction, there are two parties that remain determined to take on chavismo: Primero Justicia and Voluntad Popular. Both have been decimated by bribes, persecution, and exile, and both face disruptive internal fights for the leadership. UNT and AD are more favorable to negotiating with the regime if that will allow them to cohabitate and survive. Henri Falcón’s Avanzada Progresista and a bunch of little parties are working to become a third option that, in exchange for serving as the loyal opposition, would displace VP, PJ, UNT, and AD.

The more radical opposition parties spend more and more of their time trying to survive, and less and less trying to fight the regime. The off-ramp of accepting bribes and a comfortable life must look better and better as an alternative to life on the lam to many rank-and-file opposition politicians.

What leverage does the opposition have at home? What kind of influence and range does it have among Venezuelans?

Unable to influence policy, as a normal parliament would, the AN is limited to approving specific initiatives with uncertain results, such as the agreement to collaborate in the COVID-19 crisis between its health adviser, epidemiologist Julio Castro, and the Health Minister. These days NGOs do much more, so the AN has become largely irrelevant to Venezuelans dealing with life under hyperinflation, shortages, power outages, endemic violence, disease…Venezuela’s biblical plagues.

However, people linked to some parties remain active in grassroot communities. Like the folks at Alimenta la Solidaridad.

What leverage does the opposition have abroad? How influential is it regarding sanctions against the regime or any other kind of pressure?

The AN has more power abroad than at home. As long as this remains true, and foreign governments keep supporting it, the parliament still has some capacity to block the Maduro government from accessing credit or assets abroad, such as the gold in the Bank of England, or CITGO.

We think, though, that the investigative journalists at ArmandoInfo were more influential in generating U.S. pressure against Alex Saab than the AN, and that both the regime’s pressure and the unending internal squabbles will gradually degrade the opposition’s influence abroad.

What to expect for the rest of 2020?

We are likely to have parliamentary elections on December 6th, with little international recognition beyond the usual suspects, such as Russia and Cuba. Maduro will have a newly pliant AN with more deputies, alongside a parallel opposition run by the people Alex Saab bribed. This new rubber-stamp AN will sit at the Legislative Palace and play its assigned role. Some familiar names will be in it, cohabitating with the dictatorship; others will see their influence wane within their states and parties; and there will be those who will leave the country and try to form a “government in exile”. Either way, the dream of transition is dead.

At the end of 2019, many Venezuelans were starting to get used to the idea of some sort of cohabitation with chavismo marked by transactional dollarization and economic non-reform. It was a quiet interlude for chavismo.

Stabilizing the economy will remain a top concern, but achieving it will be a tall order with the U.S. sanctions still in place. And that’s where one would think things could get more interesting. How far will chavismo be willing to go in return for a relaxation in sanctions?

Should opposition politicians assume that a transition is impossible, abandon that path, and go back to negotiating with Maduro and the U.S. to create livable conditions in Venezuela? It’s tempting. But chavismo will surely burn any such bridge, as it has done in the past when a negotiation requires that they make any painful concession.

The big question here is whether it’s even possible to do opposition politics in Venezuela in 2020. What can you do beyond pandering to the Twitter echo chamber, lobbying abroad for recognition and sending out invites to Zoom meetings with prominent figures? While the ability to secure assets abroad is key to any transition, transition won’t happen in a foreign court room. All politics is local, except ours. Without leaders on the ground able to rally Venezuelans in Venezuela to the cause, the dream of transition will remain out of reach.

By the end of 2020 we are likely to find ourselves facing yet another unprecedented crisis: the opposition will control an expired National Assembly, with legitimacy issues, and no power on the ground, and chavismo will have a hollowed out National Assembly, elected through a rigged election, with little to no influence abroad.

A weak state is a dangerous state. Any vestiges of economic cohabitation will surely be thwarted by intervention and expropriation, and political cohabitation is not something chavismo even understands, because every time it feels threatened, it bites. Domination/submission is the only language it understands.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate