The Failed Coup That Changed Our World

Thirty years ago, we were violently woken up by an armed revolt that ended up transforming our nation, and not in a good way. A date that can’t pass without another comment

In the early hours of February 4th, 1992, a group of military and police officers led by Army lieutenant colonel Hugo Chávez tried to topple the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez, who had been elected in 1988. Before the fighting ceased in the afternoon of that day with the surrender of Chávez on live TV, at least 14 people were killed.

Journalists, researchers, artists, politicians, and intellectuals have extensively documented what chavismo has done during this time, especially after Chávez came to power in December 1998. Caracas Chronicles was created precisely to join that massive, ongoing effort of telling the history of Venezuela under chavismo. There are thousands of articles, papers, books, and movies on the matter, and we can expect we’ll never cease to bitterly debate the balance of the chavista era.

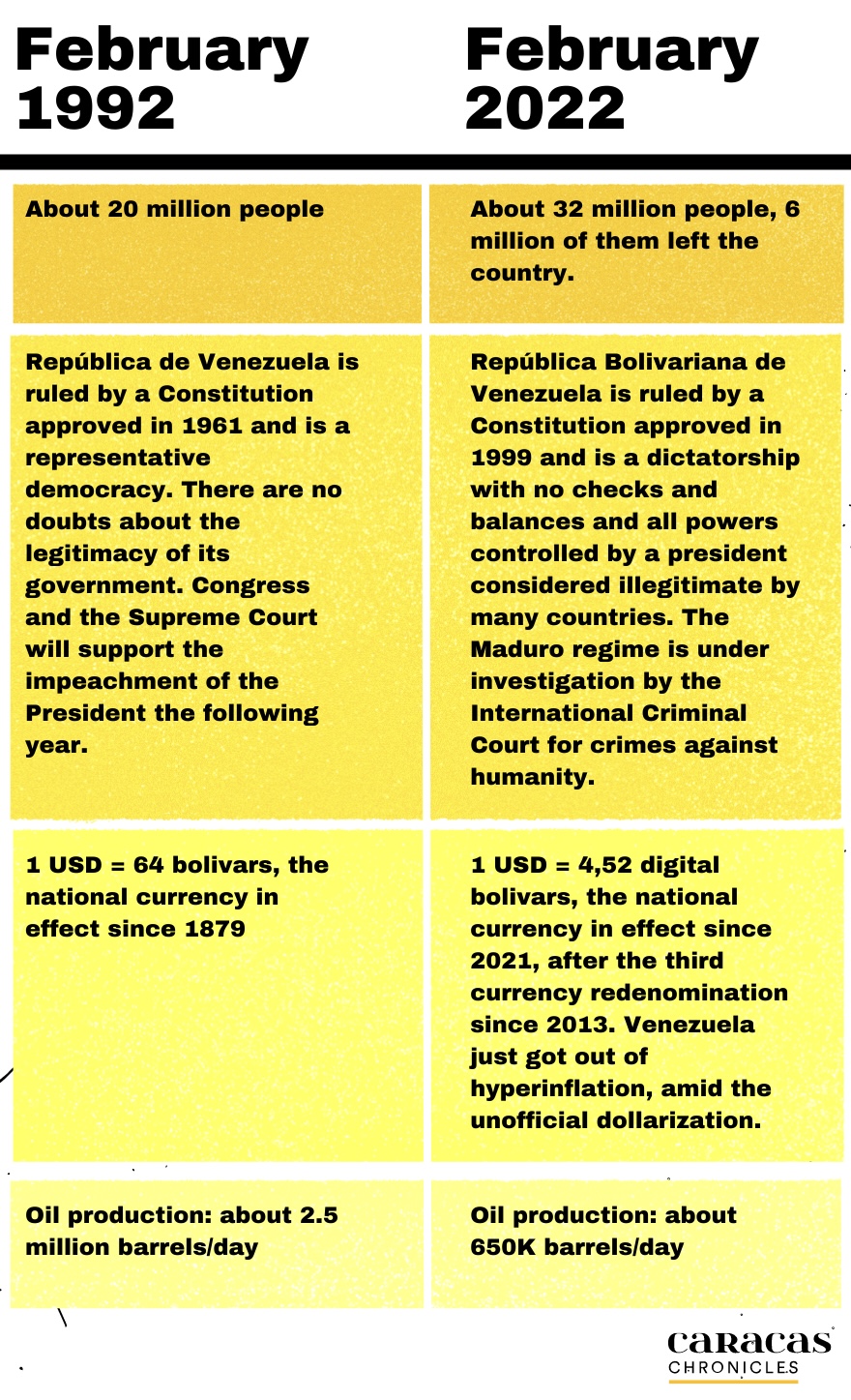

All our lives have been affected by the decision made by those men who chose violence to try to come to power. But time gave us some distance to assess the historical weight of the failed coup of February 4th. Perhaps the best place to start is by taking a look at the most essential differences between the country we had that morning, and the country we have now.

Another interesting way of looking back at 4F is how it altered the political Zeitgeist in this part of the world. Mind you, coincidence is not causation; the wave of democratization in our region was about to face a good deal of painful adjustments and setbacks had to do with the specifics of every country, the weakness of the young democratic institutions, the economic inequality enhanced by debt and mismanagement, the endurance of the military logic that tried to restore dictatorships. The failed coup in Venezuela didn’t spark the fire of chavista ideas in Latin America and the Caribbean; that would happen once Chávez was elected president and had oil income to promote his movement abroad. However, by revealing the extent of the crisis the Venezuelan democracy was experiencing, the 4F shattered the impression that the whole region—with the exception of a Castro regime surviving the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991—was walking towards democratization.

The failed coup of February 4th—or 4F, as we called it in Venezuela to gain space in newspaper headlines—revealed to us and to the rest of the world, maybe with more eloquence than the brutally repressed Caracazo in 1989, that our democracy was falling apart.

Yet it endured long enough to allow those same men who tried to get to power through violence to organize a political party, compete in regional and presidential elections, and get elected to govern. It was our democracy’s swan song: after providing to the people who chose violence the pacific means to achieve their goals, our democracy got a countdown to self-destruction in exchange. Chavismo failed in February 1992, but they were given a peaceful bridge to power and burned it after crossing it.

Thirty years ago, the exception in its place and time that was Venezuelan democracy walked into death row, escorted by chavismo and its many accomplices. So much time has passed that millions of Venezuelans today don’t know what that democracy was like, and its fading memory is so polluted that young Venezuelans are building their political identity on the nostalgia of something they didn’t experience: the military regime of the 1950s. It’s our job to preserve the memory of how our democracy was, to think how to make it better if we ever have the chance, and ensure that 4F didn’t mark the end, but a pause.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate